fugitive bubble have questions about your supposed conviction

Two-thirds of the Olympia art-punk band discuss staying in a band with your ex, the importance of saying what you mean in punk rock, and more.

I wandered around the downtown area of Olympia, Washington the day after Juneteenth; red, black, and green flags flapped in the early summer breeze all over its streets. Although it’s being built up brick-by-brick—as Seattle (and even its working-class sister city Tacoma) become increasingly unaffordable and upper-middle-class white people continue to move south—Olympia’s countercultural community has always had a strong foothold in social justice. If I were in any other city in Washington State, I’d be a little surprised by such a clear display of solidarity with its Black community.

Thus, on this lovely June 20th afternoon, white people smile at me with enormous cultural subtext as I make my way from a solo dinner at a bougie restaurant on Capitol Lake to the meetup spot I’ve arranged with the members of Fugitive Bubble. In the alley behind locally renowned venue/vegan diner/dive bar Le Voyeur, where any punk worth their weight in cauliflower buffalo wings has played on a stop in Olympia.

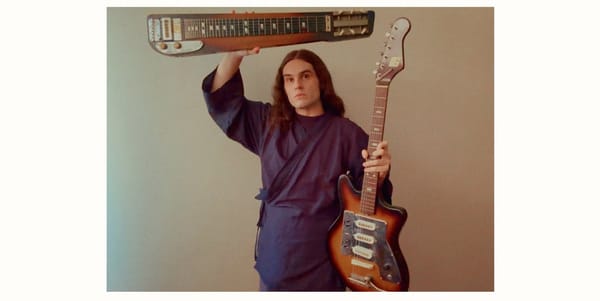

After a few minutes of waiting in the alley where teen punks would watch the 21-and-up shows through the normally-wide-open back door, Kurt Stevens (guitar, vocals) and Harley Moore (bass, vocals) entered my line of sight, striding together about a quarter-mile down the alleyway toward me. Typhoon Mary, the band’s drummer, was nowhere to be found, which seemed kind of weird to Kurt and Harley, because it was Mary’s idea to meet behind Le Voyeur. (Turns out Mary was double-booked and attending dinner with family.)

Some people call it dumb luck, others call it divine timing. Whichever the case, I found it to be significant that I chatted with two-thirds of Fugitive Bubble the day before the man who swindled his way into the United States presidency (twice!) ordered a strike that would, at least temporarily, put our country on the doorstep of WWIII. A big part of the 35-minute conversation I had with Harley and Kurt involved our love for bands that say what they mean and keep a watchful eye on the state of the world—particularly bands like Crass and Minutemen. And their latest album is a direct result of practicing what you preach.

What Would Happen If We Stop?, released in April on Sorry State Records, speaks to the idea that the personal is indeed political throughout its runtime, particularly on songs like “Rot,” “Failed Experiment,” and its climactic title track. The second of those songs ostensibly features not only the central lyric of the album, but arguably the thesis statement of 2025: “How can you say you’re sane/In this crazy world?/How can you say you’re sane/In this fucked up world?”

If 2023’s Delusion—rife with bangers like “Fishbowl” and “Chickenhead,” the latter sounding like riot grrrl anthem 30 years too late to the party—evoked the feeling of punk lifers finding their ideal musical partners and creating an insanely worthwhile punk rock album, What Would Happen If We Stop? marks the arrival of a punk opus with the ambition of your favorite peak SST albums. The songs highlight a society in decline and the resilience we as humans (who actually employ humanity) must have in order to preserve the things we care about.

After grabbing a booth in the front of Le Voyeur, Kurt, Harley, and I talk about the two of them forming Fugitive Bubble in the midst of a romantic relationship and working together in its aftermath, a lot about their recent opus, and the need to say something real when you have the platform to do so.

What led you both to Olympia?

Kurt Stevens: Well, Harley was already in Olympia, but I moved to Olympia for one year in 2015. And then I moved away; I was living in California, uh…

Harley Moore: He was trimming weed.

Kurt: Well, yeah. I was growing weed.

I had a friend who’d trim weed on occasion. It’s pretty lucrative, actually!

Harley: Is it OK that I just said that? Maybe don’t include that.

Kurt: No, it’ll be fine. I was basically on Instagram and I made a comment on [Harley’s] story. And then we just started talking like crazy. After a little while, we fell in love and I moved up here. We were together until like a year ago.

Harley: We dated for six years and then we broke up. But we still love each other. And we're still doing the band and we want to play music together forever, and we hang out like once or twice a week, still.

I love that you’re still friends and you still love each other. And you’re still committed to collaborating. May I ask what happened to dissolve the relationship?

Kurt: Over six years is a long time. I think it was just a few things that lasted an extensive period of time that were just not going to work out for both of us in a relationship.

Harley: Yeah, but I feel like it’s funny because I feel like we’re just friends. And we always were best friends. And then we always vibed so well musically. On tour, we work the same. We’re both obsessive in the same ways. We write music in similar ways. I think we just realized that’s what we are: best friends and musical collaborators.

Kurt: It definitely felt better.

Harley: We stopped fighting! We stopped fighting! We were fighting a lot and now we don’t, so that’s good.

That’s great! I feel like you don’t have to be romantically involved to be soulmates.

Harley: I came to Olympia because I didn’t know where I was gonna go next. I just had a friend who was like, “I have a room for rent.” At the time, it was $300 a month. That doesn’t exist now. And then I got a job really easily and it was just the easiest place I could move, ‘cause it was so cheap at the time. I lived in Seattle [prior to moving to Olympia].

That’s when you were in Vats.

Harley: I was in Seattle playing with Vats. And then Vats broke up because everybody at that time—in like 2016—was moving away from Seattle. Office Space was a venue and it had ended. A lot of bands were ending and a lot of people were moving away. All my friends moved away at the exact same time. So I was like, “I’m gonna move away too.”

And so you ended up in Olympia.

Harley: I guess so, yeah. I didn’t think I was gonna last this long here.

I mean, it is changing. It’s so weird to come to Olympia and see the expensive cafés with all the bougie stenciling on their signs.

Harley: Like the “ampersand businesses.”

I’m pre-grieving the old, cheap, shitty Olympia.

Harley: Yeah, yeah, for sure. We are too.

Kurt: Yeah, I'm originally from Buffalo, New York. Definitely was extremely cheap to live there. And then I ended up out in Portland in 2008 and it just happened to be as cheap as Buffalo, so I stayed there. It was pretty cool. Fun to be a kid there.

What did you do out there? I heard you’re big into skateboarding.

Kurt: Yeah, I basically skated a lot.

Harley: Kurt was in a famous band in high school.

Kurt: It wasn’t famous.

Harley: Yes it was.

Kurt: It was called Skate Korpse. You know, there wasn’t all the shit on the internet. And a lot of people took a liking to it. I wouldn’t say we were famous.

Harley: Yes you were!

Kurt: Nah, but we put out like four singles and somebody put out a discography record. People liked it, but it was definitely short-lived.

Was there a musical or aesthetic direction that you wanted Fugitive Bubble to go in?

Kurt: No, there wasn’t really.

Harley: We have too many influences and our interests are so vast. We both really like—you’re more ‘80s hardcore, but I’m more Kleenex/Raincoats. So we definitely kind of had to collide both of those [influences], but then we both really like all kinds of other shit.

Kurt: I like to add a lot of peace punk.

Harley: Yeah, we like Crass. Like any Crass record.

Kurt: We didn’t say we wanted it to be a certain style. We just played.

Harley: Whereas Mary is a D-beat person and a crust person and had never even listened to Kleenex or the Raincoats before entering the band. They had listened to ‘80s hardcore, but is more on the metal, D-beat side of things. But now, they listen to more stuff.

That’s cool. I like that you are referencing Kleenex and the Raincoats, because they’re two of my favorite bands of all-time. Especially Kleenex. Kleenex is probably Top 10 all-time for me.

Harley: But we want to be faster and more hardcore punk than that.

Yeah, and you definitely are. What are your feelings about Delusion and what do you think when you go back to revisit it?

Harley: I think about writing music with [our previous drummer] Perry because we were pretty serious [about this band]. We were writing and playing with him all the time.

Kurt: I guess I don’t really think about it too much other than [when] I periodically listen to it, I’ll be like, “Is this still good?” And I’m like, “Yeah, it’s good. It rips.” I was listening to it today. I play in other bands too, and I’ll be fucking just trying to write way too much shit. So my whole thing is, once it’s out, I’d rather just check back to see if I still think it’s dope or whatever. I’m two records ahead.

Harley: Kurt could sit and write 10 songs a day if you didn’t have a job or anything. It’s like, you’re fast. You’re really fast.

Kurt: I like to write different styles, so I have different projects.

The new album, What Will Happen If We Stop? has really been catching on. It's been really cool to see. I think one of the things about it is that it's immediately recognizable for its musical ambition. Was that a conscious thing or was it more, again, you getting in that mode?

Kurt: I mean, consciously we did want to make an exciting record, you know?

Harley [to Kurt]: I feel like it’s you. Something that has happened over the years is that you always want to push further; more, more, more interesting, more intricate, more different, more unique, more.

Kurt: And just simpler and making it have a variety of sounds, but have it still sound like us.

Harley: I feel like I’ve been freaked out in the past. I’ve been like, “What if people don’t like it?” Because it’s too weird. But [to Kurt] you don’t give a shit ever. You don’t care. Kurt just doesn’t care what people think. I think that’s why it’s so special. I really do.

Kurt: I also really like—you know Larry Heard? He’s a house guy. He has this one record where he has this monologue that starts it off. And it really hits strong with me, and I think it portrays a good point of view for songwriting and creativity. I obviously don’t have it verbatim, but it’s something to the effect of, “We always want to put out the best thing we could do, but it’s not always gonna work out that way. And we should be fine with that because we created it and then it’s something we can look back on and move on from that.” And that’s fun to do that. He also has a label called Guidance and it stands for Growing Under the Influence of Dance, and I think that’s the freshest shit on Earth.

Yeah, it’s a document in time. I feel the same way about writing and visual art. You’re capturing a moment. It’s like a time capsule.

Harley: Once it’s out, you birthed it, and it’s done. You can’t change it. I’m happy with it, though. It’s funny, because every time we write and release something, I personally can’t tell what it sounds like. I don’t even know what it sounds like until we go on tour and we’ve been playing it a lot. When we play a bunch of shows, I can feel like I can hear the songs, but I can’t even tell if it’s good. I just blindly trust that Kurt and Mary would tell me if it sucks. And then over time, maybe we don’t know. I just have to trust that it doesn’t suck.

I was going to ask you if you’ve reconciled your fear of your music being perceived as too weird.

Harley: Currently, it’s not weird at all.

Kurt: Normal as hell! [laughs]

Harley: I think over time—the repetition of it and how many times we’ve toured and how many times we’ve released shit now—I’m more calm about it. I’m not as anxious about it. Because it has gone well. I don’t want to sound like a hater, but so much of the shit that comes out is fucking boring.

This is a safe space for haters. A lot of the shit that comes out right now is fucking dull.

Harley: It’s fucking boring! And no one’s saying anything! No one is saying anything that they mean, you know? And now is the time to say shit that you actually fucking care about.

Kurt: At the very least, I feel like [people should] show—

Harley: Vulnerability

Kurt: An ambitious attempt at writing some music.

Harley: Try. [laughs]

Harley, you mentioned bands not saying what they mean, and one of the things I love most about this record is your lyrics, how you both are saying what you mean. And I was wondering if the fuckery of the past few years inspired that, or is it more of, “Hey, I need to get this off my chest.”

Harley: I mean, yeah, politically, everything is fucked up. But I think good music should be vulnerable, and you should push yourself to be real and say what you are actually afraid to say. And then it will probably be good music if you do that. Because if you’re making music that’s basic and fucking repeating an aesthetic, you’re probably not gonna say what you need to say. And, I don’t know, if you have a fucking platform, I think it’s fucked up not to use it to say some shit.

Yeah, my therapist always tells me the scary thing is the worthwhile thing.

Harley: Exactly. I feel like if I’m too scared to write something in a song, that’s what I probably should fucking write about then. Sometimes we write lyrics together, we did that last week. We got together and it was just fun. We usually have an argument, but then through the argument we’re passionately arguing, and we come to a really good thing.

Kurt: When I write lyrics—I’ve been into punk since I was 15 and what I wrote about then and what I was angry about then hasn’t changed really. When I was a kid, I would write straightforwardly and I would use political vocabulary and stuff like that. And I feel like now—I like Minutemen, I always have, but I am deeply inspired by how D. Boon writes lyrics. And I feel like it’s prose, but [with] social, political, and class issues and stuff like that. And thinking [about those] things, but speaking them more artistically.

It’s funny that you mentioned Minutemen, because the one lyric I can’t get out of my head is from “Paranoid Chant”: “I try to talk to girls and I keep thinking of WWIII.” That’s the sign of the times right now.

Kurt: And that’s funny and cool, but it provokes thought too. And you’re just like, “That’s smart.”

A lyric of yours I really love is, “How can you say you’re sane in this fucked up world?”

Harley: Kurt wrote that song, actually. I was having trouble coming up with lyrics, but the song [had] almost like Crass-style sections, but with a lot of stopping and starting. And so I was thinking of political Crass lyrics, but I was also thinking about—I work as a therapist and I was thinking about how my job is to help people feel more sane, but I don’t really think sanity is possible.

Sometimes it feels like we’re living in the end times. And I think coaching people to feel sane in these times is almost toxic positivity.

Harley: I think people just thinking everything is OK is actually insane. If you’re living right now and you think everything’s OK, something’s wrong. I think Crass has like ten songs about this.

Aside from what the title track says, what does the title What Will Happen If We Stop? mean to you personally? I have a lot of thoughts and feelings about this myself.

Harley: The song, What Will Happen if We Stop? is, “What will happen if we stop working?” “What will happen if we stop believing in the people in power?” “What would happen if we stop believing in the narratives that we're told?” “What would happen if we stopped going along with the shit that we’re fucking fed?” Like, “What if everyone just stopped fucking going along with it?” What would that look like? I want to dream about that. Come on guys. Like, come on. I just feel like I wanna get everybody to like to dream about that together.

Kurt: Yeah, that sums it up. What would happen if we stop believing in ourselves, too?

My thought when I first saw the title was, “What would happen if we stop persevering? What would happen if we stopped trying to make the world a better place?” Which is the flipside of what you’re saying, I guess.

Kurt: I had my own interpretation of it and obviously I think all that stuff, but also I think, basically you just have to. t’s good for everybody to keep moving along in a direction that you feel is positive. For a community of people, not just for yourself.

Harley: In the song, I think the lyric is, “Authority, what would happen if we stopped needing you? Authority, what would happen if we stopped believing in you?” So it's kind of like, we just believe that we are being controlled. But what if we stop believing that we're being controlled and we just actually realized that we could stop?

see/saw is a reader-supported publication, so please consider a subscription to support this independent punk journalism operation!