haram will not succumb to despair

“That’s the common thread between punk and the Middle East... you don’t give up and you keep going, and you need to be prepared to give it all.”

Tucked inside the bandshell bowl at Herbert Von King Park in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn, I look up from my phone to find myself in a sea of black clothing, tattoos, and body odor. A smattering of families with toddlers hover just outside the pervasive clouds of smoke. It’s the early evening of September 11, 2025, and the band has just finished setting up. Signs declaring “FUCK ICE” and “FREEDOM PALESTINE” adorn the back wall of the stage. When Nader Habibi strolls onto the stage in a long black kilt, the guitars ring out and the mood shifts. The pit opens up, and a scowling punk with flowing curly hair ignites an Israeli flag. It’s time for Haram.

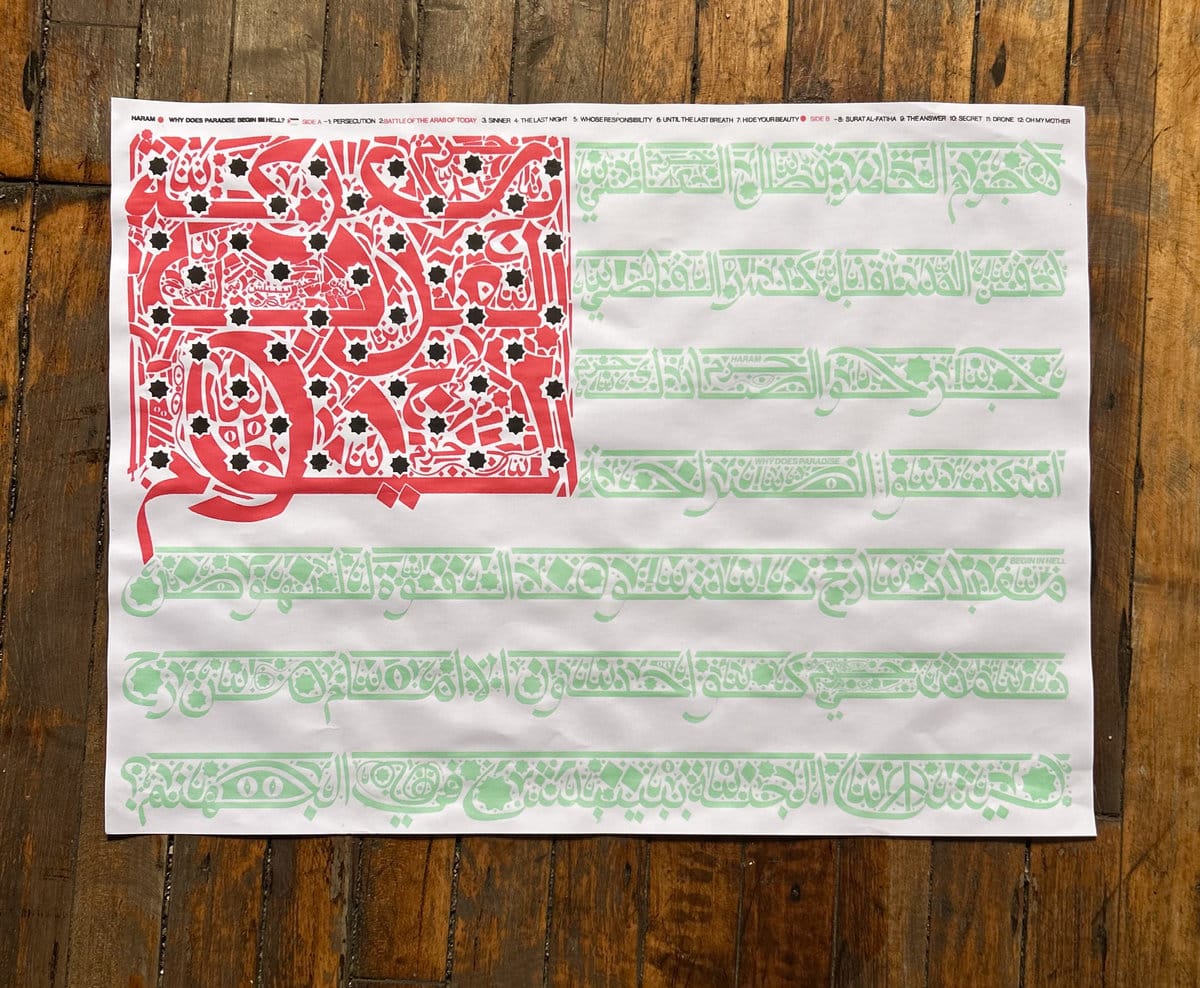

The show is the record release party for the Why Does Paradise Begin in Hell?, the new full-length by Haram, an Arabic hardcore punk band from Brooklyn, New York fronted by 34-year-old Lebanese-American Nader Habibi. The Arabic word “Haram” translates literally to “forbidden,” a representation of everything deemed impermissible by the laws of Islam. For the past decade they’ve been challenging audiences with raw, relentless hardcore sung completely in Arabic. What started as an outlet through which to channel Nader’s violent feelings of resentment from coming of age in a post-9/11 New York City has turned into the nexus of an anti-authoritarian movement that resists classification as much as it does oppression.

The band’s 2019 EP Where Were You on 9/11? explored the collective trauma shared by the world on the day the World Trade Center was destroyed through his own experience as a Muslim in its aftermath. The new LP zooms in on his own personal struggle—the jihad he sings of on the 2019 EP—contextualizing it within the struggle of his people on a global scale, as well as the genocide in Palestine. “I may never understand the struggle of someone being actively murdered,” Nader tells me. “But in my own experience, I have the same mentality. When I go up on that stage and I play with other bands who are joking around, like this is whatever they do after work… I’m prepared to die up there. I’m willing to give my life for what I’m doing. And I’m serious about it. It’s a very dangerous band.”

That danger is largely ideological, so far limited to their confrontational lyrics and performances; their sound is both propulsive and punishing. And you’re more likely to get picked up than beat up in the pit, which was populated with many flavors of outcast that afternoon in the park. This basic truth about the band didn’t stop the FBI from opening an investigation into Haram, Nader’s family, and his friends after the release of Haram’s demo tape in 2015. Evidently, someone in charge was spooked by the black-and-white design and Arabic characters at the height of ISIS hysteria. Finding no evidence of any wrongdoing, they moved on and haven’t harassed him since.

But it would take years to repair the rift it created with his family, who didn’t understand Haram or his own jihad. “At a certain point in my life, I could have easily been one of those people that caused harm,” he says. “We have a very bloody history, as a species and as a country. So there was definitely a time in my life where I thought that if I want to make a statement, if I want to be popular, if I want people to pay attention to me, I have to hurt people. I have to hurt the people that hurt me. But I turn that into a peaceful form of expression and art, and I think that’s really important.”

A few days before his record release show, I met with Nader in that same park to discuss Haram, his youth in Catholic school, and his relationship with both punk and Islam. What follows is an edited transcript of our conversation.

You and your siblings attended Catholic school as practicing Muslims. How did that experience shape you?

I was born and raised in South Yonkers. I grew up with nothing to do with punk. I was not exposed to it. I was born to Lebanese immigrants. They came from the Beirut area, and I grew up Muslim—Shia Muslim. Between Sunni and Shia, it’s the smaller one, and it’s an even smaller community in Lebanon. They sent me to a Catholic school called St. Matthew’s for the first half of my life. They heard that the public schools and Yonkers were no good, and they thought that would be better for me. And that’s where the story starts to go downhill.

I always felt rebellious from a young age. I would go to mosque on Fridays, and every first Friday of the month, the whole school would go down to the church that was connected to the school. So there was always one Friday every month where I would go to church during the day and go to mosque right after. I was what, eight or nine? I remember feeling like this was where my memory turned on—where I was like, Nah, there's something up with this. I don't trust the information that I'm getting. I’m going to church. I’m going to mosque, and they’re telling me two different things. They’re both telling me the other is wrong. So there was this immediate distrust in what people told me was correct. That’s where my journey in punk started.

I didn’t get put onto the music until I was 17 or 18—late, late, late in the game. I was wearing khaki shorts. I was not in it at all, but I felt different. So when I got exposed to punk, I immediately fell in love with it. I was like, Oh my god, what is this? I remember going to my first show in Brooklyn, in Bushwick, at 538 Johnson. I don’t remember what the show was. It wasn’t the bands that turned me. It was the fashion, it was the fucking camaraderie that came with the music. It was the drugs, it was everything. It was the freedom that came with it.

The things that were forbidden…

It was taboo. I was attracted to this forbidden fruit. Coming from such a strict childhood, where my parents very diligently sent me to school and set me up on guardrails. No alcohol in my house, barely caffeine. You know what I mean? It was very strict. So I was attracted to this lifestyle, for sure, I didn’t get too deep into it. I always held true. And I felt almost like a prisoner in these beliefs, to the core Islamic tenets. Because that was so ingrained in who I was and who I still am that I can never get too far away from that. Even in the midst of my involvement in punk, I’m never a big drinker, I never did serious drugs. I just kind of always held true.

That sounds familiar to me. “Cultural Catholicism” is big in Latine families, even when you’re not practicing there are symbols and rituals that can carry meaning.

Christianity—and Catholicism, specifically—that was a huge part of my life as well. I'm drawn to sitting at church. Sometimes I like that. It gives me comfort from when I was a child. I still identify as Muslim, and that's also a very controversial thing. That’s how I got into punk. I remember going to that show and being like, Holy fuck, everyone is weird. Every single person has their own set of oddities. And I felt comfort in that. I felt like I’m not just in the midst of all these normal people where I have to explain who I am.

And that is really where Haram started. The mentality behind the band is that I always felt like I had to explain who I was and what I do and where I come from. It always had to come with an explanation for people. You have to provide a context, always. And I can never just be accepted for who I am. Haram started on that principle of “this is a question mark.” This band is not an answer. You know, it’s more. So you come, you watch this band, you have your own opinion, go ask someone that speaks Arabic about it. I don’t know. I’m not gonna tell you.

Like many Muslims in New York, 9/11 shaped your experience in a pretty frightening way. What did that look like for you specifically?

Before 9/11, my school wanted to be able to be like, “Look, we’re a Catholic school, but we have this tokenized Muslim kid, send your kids here, please, we need money. And then after, it was like, “we don't know them,” you know what I mean? “We don’t know how he got here.” No one stood up for us. And we were going through crazy times. I was in fifth grade.

I was physically hurt, for different reasons, like being called a terrorist and bullied psychologically. It didn't really have a crazy effect on me, I want to say, but the anger was in there. It turned me into someone that was resentful. Resentment gets people to do very stupid things, and there’s no outlet for people like me with a fucking spurned identity in post-9/11 New York. An Arab Muslim kid? There was no outlet. And when I found punk, when I found this revolutionary music and counter culture in general, it gave me an outlet, but I still didn't feel like I fit in. In a counter culture. And that is crazy.

After Haram, I had a place to put those feelings, violent feelings of resentment that I didn’t know what to do with. And I argue that’s where the jihadi mentality comes from. Young people, like the Pulse [nightclub] shooter…there are these young Arab men that grew up Muslim and turn into radical Muslims because they have no outlet. And Islam provides you an outlet in a way. If you take it in a certain direction, it could be violent, for sure. For me, Haram is an outlet for people to use as a way to express themselves, as a place to put all these negative, angry emotions. That’s just for the Arab people, for Muslim people, for any oppressed person.

You were working on this new record Why Does Paradise Begin in Hell? as the genocide in Gaza filled the streets with blood and rubble. How did their struggle influence the album?

The record speaks heavily about the genocide—that’s really when we started writing it. In the booklet in the insert, there’s pages dedicated to the journalists that have lost their lives. If you hear what these people say, these people that are fucking being ethnically cleansed, they’re saying, “We will die for this land, and we will go through this and this land will be paved with our corpses for the hope of that future.” No matter what, the plight of man is to suffer, and to achieve through that suffering. I truly, wholeheartedly believe in that. So the record is about that.

On a personal level, I had a really rough time these last five years, through personal health, mental health, life stuff that we all can relate to through the pandemic, even. I learned some harsh lessons in life, and I think that with a lot of work, eventually we can get through it, no matter what. I really believe that. So it’s kind of a motivational album. It’s meant to be optimistic. The lyrics of that album contain a lot of personal experiences as well as political battles that my people are facing at the moment.

How do you manage to engage with that—genocide, ethnic cleansing, murdered journalists—and not succumb to despair? How can you still believe the struggle will heal you?

It’s about persistence. That’s what I’ve learned. You’re not always gonna get it. But in the same way people are giving up their lives in Gaza and Lebanon, in Yemen, in Syria, in all these places, this is the global cost. It comes with persistence. It comes with never giving up and putting everything on the line for the sake of what you believe in. And that’s the common thread between punk and the Middle East and the conflicts and whatever, you know? You don’t give up and you keep going, and you need to be prepared to give it all.

What you’re describing, that’s jihad, isn’t it? The struggle?

In a way. I believe in jihad in a sense. For me, jihad is a personal struggle, and that’s how it’s described in the Quran. Of course, jihad now is described as this radical fatwa to kill all Westerners or whatever. And you can interpret the Quran in that way, but I have always taken jihad as a personal battle against oneself—your own desires, your own sins. There’s a lot of things to juggle in terms of your own discipline. I think it’s a beautiful thing, and it’s very important. But I try not to use that word too much, because of how we are all ingrained with that other definition. But I do believe it’s persistence, not thinking about the prize, but thinking about how I need to get up and do this every day. I need to get up and try to survive. I need to get up and try to find food and water. I need to get up and go to the food aid distribution line. You don’t think about 10 days from now, because you can’t. You think about how you can get through today.

You were famously investigated by the FBI at the peak of ISIS hysteria due to the Islamic imagery on the cover of your demo. The investigation yielded nothing, but it must have had a lasting effect.

ISIS was the hot thing, the new boogeyman. In 2015 when we put that demo tape up, it was black and white, and you could maybe see how, like, a fucking moron could look at that and think ISIS because it's black and white and Arabic. The FBI went and they harassed my parents, and we didn’t talk for seven years. I had no connection with my family, really.

That’s something I don’t really talk about too often, but me and my family, including my siblings and my extended family of tens and tens of people in Lebanon and Canada, we didn’t talk at all. They gave me a choice. They said, “Hey, we recognize that you want to do this punk stuff, it’s so different from what we came here to do. It’s not the path that we paved for you. We didn’t come here and suffer for you to do this, you know?” They said, “You’re gonna hurt yourself, and you’re gonna hurt us as a family.”

I believed in it so much that I was like, I have to go my own path. I did the first half of Haram with no connections to my family. And that was another layer of feeling ostracized there too, constantly feeling like at any point, something could happen to me and they’re gonna go after them. I was born here. I’m naturalized. They were not. They could be deported in a second, if they really wanted to, so I did it with a lot of risk, and my bandmates supported me the whole way.

In the underground, people were like, “Oh, this band is a threat, actually dangerous.” In a way, the FBI put us on the map, but they never bothered us again. I had a lawyer on it for a little bit, on some real shit. They told me that there is like a file about it, but that there isn’t an open case or anything. But I always feel like I’m being watched. I don’t know. I don’t care, you know, but I feel like, in a way, that never went away.

When Haram started, there didn’t seem to be many bands you could call contemporaries. Who could you look to for guidance or influence?

There’s not a blueprint for what I’ve done and who I am, and that’s good and bad. My goal as a human being in the punk scene, my hope was that if a kid had a similar struggle to me, if they were also Arab-American or Muslim—whatever connection we had—that they could listen to my art or look at me as a person and my life when I pass and be like “he paved the way.” Where I could at least live in a way where I feel understood. That’s it. I’m not looking for anything else in this life.

At our shows, if 1% of the audience spoke Arabic, we’d be lucky. But recently there’s been a massive boom in Arabic punk. There’s a lot of Arabic punk bands, a lot of Arabic punks, even Arabic celebrities. I don’t want to be seen as a figurehead in this Arab-American community because what I do is still taboo. When we play in these Muslim majority countries like Indonesia, they’re freaked out. It’s still a counter culture to Arabic culture, you know? Not all Arabs are gonna get down with a punk band named Haram with a fucking crazy guy singing. I showed this to the deli guy and he was not happy. I was like, “Yo, it’s Arabic punk!” He was not about it. The guy is probably a devout Muslim dude that doesn’t want a progressive form of Islam or doesn’t care about a dude covered in tattoos saying he’s Muslim. We’re still a taboo band.

Right now, there’s a huge boom in the Arabic punk scene. The big one that came after Haram was Taqbir. Taqbir was started by my friend Nao; she’s from Morocco and moved to Spain and started this band. She was like 14 when she first started listening to Haram, a super young hijabi, and reached out to me to talk about what it meant to be Muslim and all this stuff. Eventually she moved to Spain, she took off the hijab, had the same thing with her family: big split. And then she started a punk band. She said, “I want to make a band like Haram.” And that, to me, is everything. That’s all I wanted.

Ikhras are really good friends of ours. The singer’s Palestinian. They’re more like a capital H hardcore band, but they’re really good. Zanjeer is another band, they’re not Arabic punk, but they still call themselves Harami punk, which is like a sub scene that’s starting now. Haram in Arabic means forbidden, Harami in Arabic means criminal—people that do forbidden things. Just badass. He sings in Urdu, his name is Hassan, and he’s of Muslim background too. So he can still relate to this movement in music. And we’re gonna play with him in Berlin in October, which is gonna be cool.

Do these other bands inspire any optimism in you?

This is now an interesting chapter that's coming up in Haram’s history, because I’m not 22 and confused anymore. I’m 34 and I have a very established form of what this band stands for, and the community that’s forming around it. A lot of people speak about this, and they’re like, “Oh, yeah, I fight for a better world,” or “I fight for things to get better.” I know things aren’t gonna get better. I’m not delusional about it, and I’ve said this my whole fucking career in music and my life. I don’t live on the principle that things will get better. I live on the principle that things are gonna get worse. And the way I look at it is: always be prepared for worse, and you’ll be all right.

What kind of effect do you think that has on someone to be so emotionally and spiritually hardened? You’re not just expecting to struggle—you’re expecting the struggle to become harder, to persist. Do you not feel that extra weight?

It’s a daily fight, man, I don’t know. It’s really hard. It’s hard to really bear the weight of it and find a way to exist. But I’ve romanticized the pain to where I see it as an entryway to better times, always. So if it hurts now, it might hurt more later, or it might get better. I don’t know.

Do you believe in God?

Not really. I believe in the concept of that, not literally. Spiritually, I find comfort in feeling that. I’m not delusional to the point where, like, my dad lives this life in order to prepare for the next. I used to be staunchly atheist coming out of high school, like, fuck all gods and this is all man-made stories. That's humanity, and the evil of man, you know, and the way that they’re able to control people. They invented this concept. And for me, spiritually, I intuitively default back to it. If I’m in a scary situation, I say a prayer. It calms me down. It’s Arabic and Muslim prayer, the ritual of it. I’ve defined my own version of Islam.

People don’t like questions. They don’t like being challenged. They can’t accept, for example, that we don’t have an answer that science can explain. We’ve heard this big bang theory and whatever, like that’s the best we got. People don’t like that. They want an answer to everything. So what’s easier to digest? God! He’s benevolent, he looks just like you, and he’s just this guy, and he makes all the fucking decisions for you. Everything is just created for you. That’s an easier reality for people to live.

You’re starting a tour right now, but Haram doesn’t really play very many shows. How much of that has to do with the live music scene here in New York?

Haram isn’t a band that you'll see once a month. We come out maybe twice a year. Now, when it's Haram time, we come out and we're playing in some fucking weird ass place. And we played in a fucking subway tunnel a couple months ago. Like 1,500 people showed up. It was awesome. Hank Wood and the Hammerheads and all these other bands played.

But we like playing these guerilla shows, you know? We're not even about venues anymore. I'm done with this Ticketmaster, Live Nation shit. The kids that are growing up in punk now, they don’t want that either. They don’t want to go to a venue and pay like $12,000 for a beer and then the show. They can’t afford it, and they don’t want to digest it in that way that we’re talking about. People are smart now. They see that and they’re like, “Oh, this is curated for me, this is a curated experience. We don’t want that.”

And not one venue that I played in 2015 is open today. Not a single one. So we have been working with different collectives in New York City to play these guerrilla shows. We just go out, we find a fucking place, we pop the lock and we fucking bring in the PA and we play. That’s what we’ve been doing recently. In the last five years since the pandemic, the cops have fucked off and left us alone because they understand what happens when you fuck with the kids here. The fucking cop cars get blown up, you know what I mean?

You’ve toured Southeast Asia and predominantly Muslim countries like Indonesia. Do you have any plans to tour in the Arab world? North Africa?

We’re trying to get a show in Morocco for this tour, and we messaged this person on Instagram, like, “Hey, I heard that you're a Moroccan punk guy. Could you get us a show?” And he was like, “Sorry, yeah, we don't do shows no more, maybe check back in a couple months. But here’s a link to a list of other venues you could touch base with.” I clicked the link, and it takes me to this fucking Matrix style, secret messaging app where the messages self-destruct in like, 45 seconds. And there they said: “Hey, Haram, we would love to do a show for you. We can’t message you over the Meta apps because they’re heavily monitored, but here’s our Signal.”

So we’ve been talking to this collective in Morocco through Signal in an encrypted chat. And they challenged us a little bit like, “Why do you want to play Morocco?” And I said, it would be nice to be an Arabic singing band and play in an Arabic country. We’ve never gotten the privilege to do that, and it’s pretty important for us to do that, because that’s where it’s gonna get uncomfortable for us as a band. We’re seeking that internal conflict. The band is supposed to be challenging. It’s supposed to challenge the audience. And I feel like here, it’s done. We’re done challenging.

So this guy replies and says, “Just let you know, we don’t speak Arabic in this country. We speak Darija, and it’s not standard Arabic. We don’t fuck with Pan-Arabism in this country.” The North African Arabic countries are very much against being called Arabs, because the Arabs invaded their country and caused massive amounts of generational, colonial trauma, straight up. So they’re very defensive about that. Then they asked “Are you Muslim?” And I said identify as Muslim, this is why, blah blah blah. And they said, “We don’t like Islam either. Islam is very anti-queer, anti-women, and we don’t fuck with that.”

And I was like, “OK, pause. We’re coming to Morocco as students. We don’t know what you’re about and you don’t know what I’m about. You know you don’t know my relationship to Islam or my relationship to my own culture and being Lebanese, especially Lebanese-American, so how about we have a show and we have dialogue and exchange experiences.” And they’re like, “Yeah, we’d like that.” And they said, “We can’t promote this show at all. There might be 15 people at this show. We can’t promise any money. We don’t know what’s gonna happen.” There’s a very dangerous situation there. They said, “We have to rent a house and say that we’re throwing a birthday party, nothing to do with a show. It’d be a secret.” And I was like, now you’re talking my language.

see/saw is an independent, reader-supported publication. If you enjoyed this feature, please subscribe and share this piece.