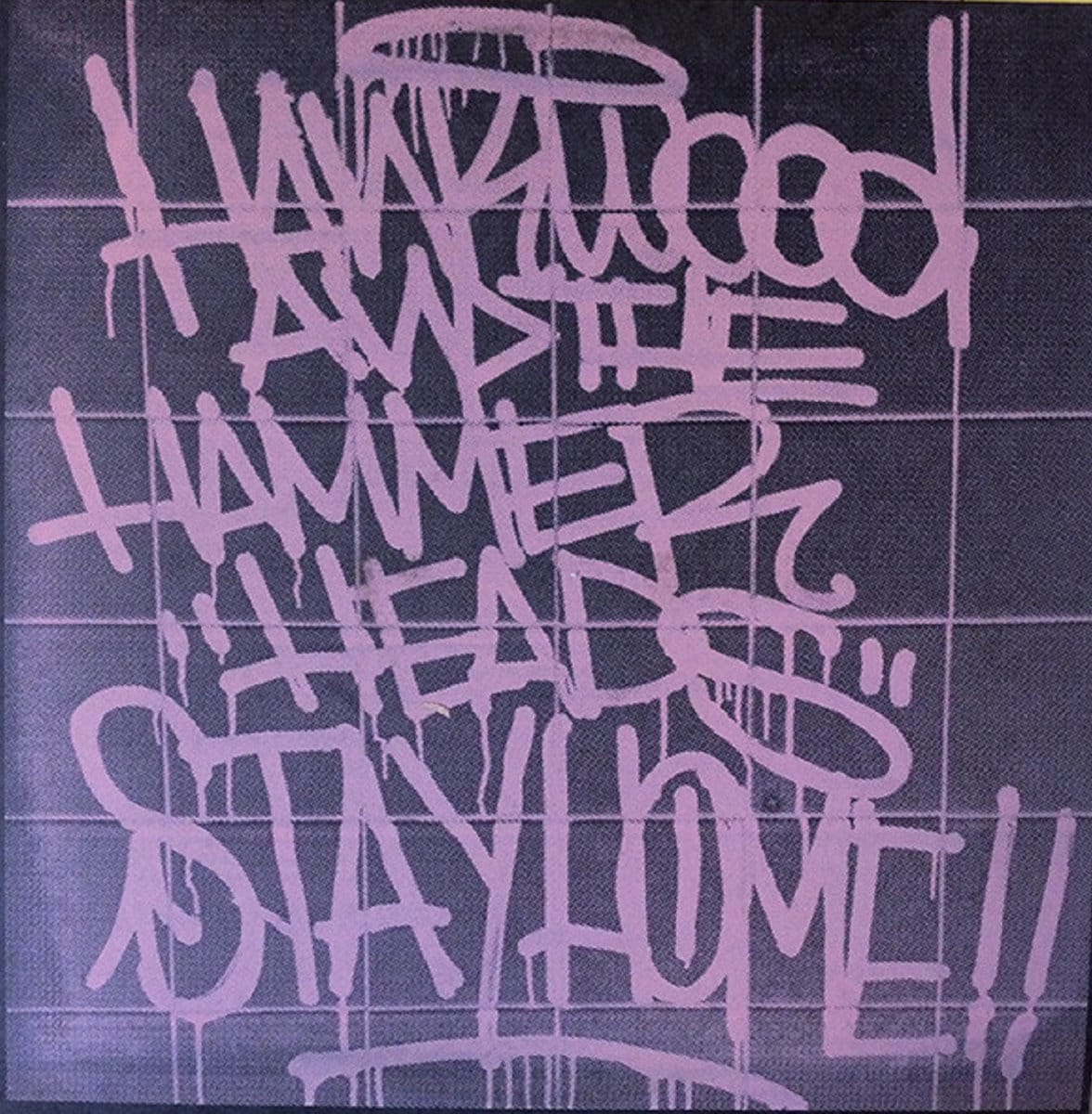

hank wood and the hammerheads’ stay home!! at 10: an oral history

The members of the NYC punk band look back on their complicated relationship with their second album and the conditions that led to its creation.

In 2014, New York City punks Hank Wood and the Hammerheads released their album Stay Home!!. Sandwiched in their catalog between their 2012 raucous debut Go Home! and their more polished 2018 self-titled album, Stay Home!! was a testament to a young punk band’s sonic ambitions.

Between the rapid fire yammering vocals of Henry Wood, the thin MIDI faux-organ leads from Forrest Byrd Looker, the ripping guitar solos from Logan Montana, the belligerent rhythm section of Max Quinn and Kevin Manion, and the wild cowbell-forward percussion of Emil Bognar Nasdor, these six dudes created a maximal, unbelievable sound. It was punk music, but the sound was without parallel in its scene and era.

Mired in darkness, addiction, anxiety, and paranoia, Stay Home!! is soulful and chaotic and dense in a way that lit my brain on fire when it first arrived. The way keys intermingle with guitar while the percussion team propels everything to the stratosphere? It’s unbelievable. I remember sitting in a bar with the lyric booklet thinking it was a concept album because of its repeated invocation of “the ghost;” it turns out its darkness is autobiographical. It remains one of my favorite albums ever. No member of the band looks back on it with significant fondness, and most of the songs have left their live show repertoire.

Forrest Byrd Looker, synth: It has a complicated place in my heart. It’s not my favorite record we’ve ever done. It represents a very tumultuous time personally and for the band.

Kevin Manion, bass: I’m not very proud of it. [laughs] It’s OK. It’s like Go Home!, but maybe a little bit more mature, which I don’t like. I like the immaturity and craziness of Go Home! a little bit better.

Logan Montana, guitar: I don’t wanna say math rock, but it’s technically the most time and effort we put into a record and we definitely learned things, good and bad, that came out in our subsequent self-titled. It's definitely when we banged our heads against the wall the hardest writing complex parts. And it was so complex because Emil was in the band—my childhood best friend, our percussionist. He’s an incredible musician and just wants to swing for the fences. A lot of that I credit to him. In a good way.

Emil Bognar Nasdor, percussion: I think compositionally, it’s really gorgeous. I think there’s some really cool compositional tricks and tools that were implemented in that era that I learned a lot from and was already instigating those tools in other projects. It was cool to see some of that bleed into Hank Wood. But I really don’t like the recording.

Henry Wood, vocals: I think there’s this feeling that we usually have, I think most of us feel this way, where there’s one song off that one that we play regularly live. I think we all view it as this weird kind of a wash. But I listened to it the other day, and I haven’t listened to it in years, and I actually liked it.

Max Quinn, drums: It feels like an interesting stepping stone for us. I think the first and the third LP have a much more obvious connection and then this record in the middle, I don’t know, it was ambitious. We were doing a lot of funky stuff with song structure and I think some of what we feel about it is like we sort of rushed some of the mixing. I think there was a way that it could have stood the test of time a little bit. I also should’ve probably listened to it this week or something, but I’m not psycho, I actually don’t listen to much of our music at all.

Henry Wood: By the time it’s done, you never want to listen to it again. I think that kind of encapsulates it perfectly. In retrospect, it is this record that makes so much sense for us. Going from Go Home!, which is just fast and sloppy punk, we were trying to do different stuff and not really knowing what we were trying to do. I think a lot of it we felt was kind of convoluted and some of the song structure is crazy. Some of the songs go on for way too long. I think we were trying to figure out where we were going sound-wise. In the self-titled record, it happened in a way that made way more sense. That self-titled record would not have happened without us being able to experiment in Stay Home!!.

Max Quinn, drums: Go Home! is such a funny record because you really can’t replicate the mojo. That record just exploded out of us. We recorded it from midnight to 3 a.m. and it was just fucking done. The second LP, we did a lot of workshopping. We actually did spend a lot of grueling time really trying to structure and hammer out that second LP.

Henry Wood: We put a shit ton of work, a lot of time, and then got super fucked up when we recorded it. That’s usually the case: You spend a year making something and then have one night to do the record it and then get super fucked up.

Max Quinn: That may be an underlying story of our band: Sometimes we’ll put a lot of work into something and then find a really good way to absolutely blow it at the finish line.

Hank Wood and the Hammerheads’ origins spawned from early friendships, but more concretely, in the kitchen of the Village institution Café Loup. It was 2009; Henry and Logan would’ve been 19.

Kevin Manion: They're about like five to seven years younger than me. Emil, Logan, and Henry were super tight.

Henry Wood: Nobody calls me Hank.

Max Quinn: That’s how I know somebody doesn’t know you. “I yeah, I met Hank one time.” Like, you might’ve met him.

Logan Montana: Me and Henry were Manhattan kids. Dawn of Humans and Crazy Spirit, for the most part they were Brooklyn guys, so me and Henry hung out all the time and lived a five-minute walk away from each other. We were both relative college dropouts.

Max Quinn: At our earliest, we would get together in the basement and eat cheeseburgers and conceptualize the band.

Logan Montana: Long story short, we’re both working in the kitchen for my father who was the chef and eventual owner of Café Loup in the West Village. Henry was on the hot line, I was on the cold line. I got him the job, he showed up on his first day in an arm cast from skateboarding and busting his ass the night before. Cut it off at the elbow himself. My dad was like, “I like this kid.” We’d been working there about six months or so and me and him were just the two of us jamming, him on drums and me on guitar. We loved the Dicks, Big Boys, cleaner guitar punk.

Henry Wood: I think we found a nice balance of being really chaotic. Stylistically messy, but listenable.

Logan Montana: The first band was him on drums and me on guitar. We just called it Bomb Diggity [laughs]. We didn’t record anything. It was just fun. He was doing what would become the Crazy Spirit drum sound. And then Max came into the picture and started playing drums, and Henry sang. What the fuck was that place called on Broadway? It was definitely with Dirty Fences who were late…who are my boys! Shout out all the guys in Dirty Fences, who we knew through skateboarding.

Max Quinn: Logan’s guitar style really dictated the direction of the band. That wild, crazy guitar shit that was sort of surfy and had tremolo. Just really psycho, rhythmically all over the. Later Forrest joined, and then Kevin.

Kevin Manion: They never had a bass player. They put out a demo on MySpace, and I was playing in another band called Pregnant at the time. We played a couple shows together at a bar called Rock Star Bar in Williamsburg; it's not around anymore. I asked them one time if they needed a bass player or would like one, and they were like, “Yeah, sure, whatever.”

Logan Montana: We were just doing “Louie, Louie” on repeat on other people’s gear until Dirty Fences showed up. Our friends were moshing and Emil showed up off the street literally with a trash can lid or some kind of debris under the train tracks on Broadway. That’s how he got on percussion.

Emil Bognar Nasdor: It was like, “Yo, we’re playing in an hour. Roll through and hit some shit.” I definitely remember bringing random objects—find a trash can lid, grab a hammer from work, whatever.

Logan Montana: We started jumping on bills under a bunch of different names. We were still working for my dad and the kitchen and my dad’s like, “Hank Wood and the Hammerheads, idiots.” Shout out to my dad Pinky. That’s his nickname. Credit him as Pinky because I’d get a kick out of that, so would my sisters and my mom.

Following the release of Go Home!, prospects for the band’s longevity did not look promising.

Henry Wood: I think we tried to break up after all the big records.

Forrest Byrd Looker: The conversation we have with the Hammerheads every time before we start writing new stuff for a new record is “do we want to keep fucking doing this.” At the end of the day when we're about to sit down and write some new material, it's like, “does anyone fucking care,” and that’s including us. That's kind of the most important question.

Logan Montana: Oh for sure, we did break up.

Henry Wood: We did break up after Go Home!, but then the record kind of took off. People really liked it a lot, then we got back together, had another last show. I think we’ve had at least two last shows now.

Logan Montana: Someone offered us a show, and we were like all right, fuck it, why not. We announced the last show, and we always used to joke, “If we keep saying it’s our last show we could sell out Brooklyn Bazaar every six months.”

Henry Wood: That was the joke after we’d done it. “Say you’re breaking up and a lot of people will come.”

Logan Montana: We did for real play a last show and say “let’s stop doing this” and get back together and say “let’s stop doing this.” It was genuine, it just became an inside joke. Make-ups to breakups. The first breakup never takes, to quote Seinfeld.

Henry Wood: I think also, we were younger. I don’t think any of us thought of being in a band as a long-term thing. We all had bands then for two years and then maybe you recorded, maybe you didn’t, and then it was like, “OK cool, we did it, what’s the next project.” Certainly, we didn’t think 15 years later we’d still be doing this.

The band was candid about the partying lifestyle that consumed them during this period.

Forrest Byrd Looker: In 2013, personally speaking, I was addicted to cocaine and I would be for a number of years after. I've been sober for about three years. I've had slip-ups every now and then but predominantly I'm clean, I'm sober. Drinking has been a huge part of my life for the past almost 20 years. I’d been blackout drunk almost every other day.

Logan Montana: Maybe my life was kind of a mess. I’m not going to say anybody else’s was.

Henry Wood: We were at that right age, that perfect age to be arrogant little shitty kids.

Max Quinn: We brought the right attitude to the moment. It was flattering that people liked our shit but we were good at not giving a shit, showing up wherever and being like, “Whatever, you suckers want to come see us play.”

Forrest Byrd Looker: Going into 2013, I think all of us were kind of like handling addictions and interpersonal conflicts based on our substance abuse. I’m also just not the easiest person to get around with and I'm kind of a piece of shit sometimes. A lot of my interpersonal relationships were suffering because of that. And when we started writing the music in 2013, I think a lot of that climate around us was getting pulled into the tunes.

Max Quinn: I didn’t see myself as a depressed or lost person at the time, but we were kind of all respectively living crazy lifestyles.

Emil Bognar Nasdor: I was climaxing into the worst mental heath time period of my life. Playing some of those riffs for months straight, it came from a very real and pretty dark place, trying to manage mental health.

Forrest Byrd Looker: We would have band practice just to run the tunes that we knew if we had a gig coming up and all of us would go out for a drink after. That might turn into the whole night and then sometimes, three or four of us would get dragged into a multi-day bender. Partying as a whole was really the climate for all of us. By the time we’re recording in 2013, there’s a bar open every night, all of our friends were out doing something every night, and we wanted to be a part of that.

Kevin Manion: I was doing pretty good. [laughs] I was getting married around that time.

Amid this party-centric period of their lives, the band consistently gathered at their practice space during late nights to work out the music that would become Stay Home!!.

Emil Bognar Nasdor: It’s very blurry, trying to draw the lineage of how it developed from me improvising every show to writing full-on parts. Stay Home!!, the reason the album is so personal to me is because that was the only Hammerheads record I did heavy writing on—guitar, keys, the compositional grit. When I think about that record, I don’t even think about writing the percussion parts. What has stuck with me was the deep three or four months that Logan, Henry, and I spent as the primary writers of that record deeply going in for these super long sessions all winter.

Max Quinn: It’s unfathomable to me now as a 36-year-old but we’d get together at 11 or midnight when everyone got off their bartending job. Everybody had these shitty jobs, and New York’s a tough place to live, everybody’s grinding out this crappy work, and we wanted to make this record, so we committed to get together at this practice space in the Pfizer building, which we shared with like 20 other bands. There was no ventilation. It was like a box. Six of us would cram in there. My memory is getting in there at midnight already feeling crazy exhausted, then going out to have a cigarette in the parking lot and there’d be three feet of snow. It was grueling and kind of grim, but it didn’t feel depressing or sad.

Henry Wood: We were partying together a lot more then. The dark lyrical shit is always in my mind, you know? I was doing a lot of drugs. Doing a lot of cocaine and drinking a lot. We were all partying a lot and remarkably, showing up at midnight and grinding this record out. It’s kind of crazy that we could still prioritize this.

Max Quinn: I think it speaks to the fact that in a weird way we were taking it seriously even with all these handicaps, like, “Kevin doesn’t get off work until 1 in the morning,” like, “Alright, we’ll start at 1:30.” And then we’d grind it out.

Emil Bognar Nasdor: All I can remember from this time period is night. It was always the middle of the night.

Forrest Byrd Looker: My favorite songs that we wrote all across our career thus far have been the ones where we'd have a night off from work or whatever we were supposed to be doing, and we'd get in the room and we'd kind of be like you know cracking jokes fucking around, and then an hour into the practice we'd finally pick up our instruments. After we freeform E-standard surf jam, every member of the band would have these spur of the moment riffs—even Henry. This has honestly been one of the most collaborative projects I’ve ever been part of.

Max Quinn: The lyrics tend to be kind of collaborative. Sometimes the crux of a song, a chorus or something, will be a thing we came up with together as a band.

Henry Wood: We grew up together in a big sense. We hung out all of the time. We practiced all of the time. There was a big chunk of time where we were living the same lives.

Emil Bognar Nasdor: We were living those poems Henry was developing.

Forrest Byrd Looker: I think they reflect what was happening to us at the time. The way we were having fucking problems in our lives. We would talk about this shit in the practice space. We'd say, “Oh man, my girl's dumping me.” And we'd all be laughing and partying. We'd be like, “You know what? It's funny because I'm the problem.” A little bit more so than the spiteful shit of Go Home!, it wasn’t so much “fuck you.” We started saying, “Fuck me. I am the problem.”

Henry Wood: I actually like the lyrics a lot on this record. There’s a couple songs about going to jail and “The Ghost” is about coke addiction. I was really into space at the time, so there’s a lot about being lonely and shit and hating my situation. Most of my lyrics are about being suicidal and being lonely. This record reeks of that. They all have quite a bit of that. I listened the other day, and I was kind of surprised at how much I liked it.

Logan Montana: We were all living in the same world, we were all going through a lot of the same problems, and we all had to agree on the lyrics. Being in bookings, I’m sure a lot of people could relate to being in a police station.

Henry Wood: I’ve been arrested a bunch of times, mostly for dumb shit. “In Bookings” is about a specific time that I got arrested that I don’t even really remember. All the being in bookings stories get all fucking jumbled up in my head. I mean, it’s just weird spats of boring time, you’re in a room for like three days and the only food you have is fucking milk. [laughs]

Forrest Byrd Looker: If my timeline is correct, we had done a bit of touring maybe a month or two before. On the way back, we were kind of finishing writing parts. We were in this little tiny cramped room that could barely fit us and our gear the day before we were set to record in Boston.

The band decamped to Boston for what they recall as two, potentially two-and-a-half days of recording with Ryan Abbot at his studio Side Two.

Forrest Byrd Looker: We were staying with some punk friends in Boston at their big warehouse. It was a cool ass loft.

Logan Montana: Future Nightmare. Yeah that was with Crusty Tim, or Ghost—singer of Sadist from Boston.

Forrest Byrd Looker: So we go to the studio, it’s a straight edge space. The first record we had recorded in our own space where we were allowed to do drugs and smoke cigarettes, and in this space we were not. That was kind of one of the stipulations of this dude's recording studio: Please don't do drugs, please don't get drunk, don't smoke, all that kind of stuff that we were so used to at that point.

Ryan Abbot (engineer, via email): Recording that record was a blast and I love those guys. I do not remember asking them to not drink or do drugs during the recording—if I did it was definitely more towards 'we have a lot of work to do' not an aversion to drugs. I actually specifically remember Henry getting the right “inspiration” for vocal takes. I don’t drink or do any drugs so sometimes my reputation precedes me, but I wasn't trying to be a killjoy.

Henry Wood: I don’t think I would have been in the studio not doing cocaine.

Forrest Byrd Looker: Dude, I mean at that point I’m used to probably doing like half a gram of coke at night, getting blackout drunk every day, maybe doing some pills along the way. And we were coming out of New York hot, you know what I mean? We would drink in the van, we'd smoke in the van, if we had drugs we'd do them in the van. Any cops reading, no we didn't.

Logan Montana: That’s the only record I’ve ever been completely sober writing and recording. That’s my story, I’m sticking to it [laughs].

Kevin Manion: I didn’t have much of a problem with it. I just knew later in the day, we’d go back to the house where we were staying and party.

Max Quinn: Were we not permitted to drink? The thing we do agree on is that this period was very fuzzy.

Henry Wood: Maybe we weren’t drinking in the studio. At least not in front of him.

Max Quinn: But if we weren’t, we were hanging out with all these Boston guys the nights abutting the recordings and those nights were late.

Forrest Byrd Looker: But yeah we were imbibing at every chance we got and I think that night before we went to Boston, we were partying. We went into that space with these raging hangovers, bleary-eyed. We were just like, “Man we're going into this hungover and we can't have any medicine.”

Logan Montana: I’ll cop to the fact that we were hungover and sweating it out in the morning, but that’s because at night, we were figuring out the parts to record the next day. That record was maybe halfway done by the time we got to Boston to record it. There were missing parts and missing lyrics, so we would stay up all night not being party animals or anything. I remember Emil, all the xylophone parts and keys parts would be staying up all night playing pool, coming up with piano melodies, bridges for a lot of the songs, lyrics for a lot of the songs, and you stay up all night doing that—drinking or not—you’re going to be sweating it out in the studio the next day.

Emil Bognar Nasdor: We had just finished learning it all.

Forrest Byrd Looker: I kind of came in and really tried to fine-tune those keyboard parts we were having trouble with. For the record and for touring, I picked up a midi controlled B3 clone wheel is what they call them. It sounded fucking weird coming from that warm real ’60s transistor Farfisa organ sound of the first record, and then going to the second record, it really sounded a little thin and ethereal, which was interesting. Our whole sound went in that direction.

Emil Bognar Nasdor: The funniest part I remember for my involvement was that because I had focused so much on writing and arranging, the percussion parts were barely complete by the recording date. I put so much less work into those percussion parts, and in the year that followed, I got so much iller at what I wanted to do on those songs.

Max Quinn: At the end of the second day I remember all of us actually having a moment where we did feel like “yeah, we really came together.” There’s a lot of keyboard parts that all of a sudden were really shining on the record. I guess the keys are pretty prominent.

Emil Bognar Nasdor: It was an issue back then and throughout the years proceeding, I always remember being really disappointed in the recording aspect. At some point I even reached out to Ryan to get the stems to redo the whole thing. I really care about the macro of an album: how things flow, returning themes, motifs, the overarching image if you were to zoom out and blur all those songs in one image. I thought it was done very terribly on the recording end. So that’s a little harsh.

Henry Wood: I have a memory of when we originally recorded it, the mix that we got back from Ryan, the keys were really low. We took it to Josh Bonati, who mastered it, and he did a lot of work to bring the keys all the way up.

Josh Bonati, mastering engineer: I remember they came over for the session at my old studio. I had that studio when Toxic State started up. Just John from Toxic State and Henry came to that session. They told me, “Oh we went to the studio in Boston and recorded, we came back and we like the mixes but there’s a couple things we want to pump up that we just didn’t have time to fix.” I think we had to boost some vocals and keys. Mastering is really your last chance to fix any problems and do any enhancements. But that record is cool to me because that was an actual attended mastering session with Henry.

Emil Bognar Nasdor: I was going way deeper into production at the time and now I do crazy production stuff. I was just like, “Man, this is the most stale recording.” It sucked the life out of it, especially after the first record which is some of the rawest, illest produced stuff from that period. I think it needed to sound more aggressive and blended.

It’s an album that stands apart both in the band’s catalog, and its sound is singular. The members of the band don’t necessarily agree on how to categorize the sound they were going for.

Forest Byrd Looker: When we were recording Stay Home!!, we kind of saw that there was not a lot of organ punk out there necessarily, let alone like garage-influenced shit coming out of New York. New York at the time really was either straight up anarcho-influenced or straight up hardcore-influenced punk music. People were not especially interested in garage influenced punk, and if they were it was happening in a different scene. Especially for Stay Home!!, we were trying to use the framework of a soul band when we recorded that.

Kevin Manion: It kind of became that way. Henry’s got soul, and we have dynamics in our songwriting in what we do. Instead of trying to be a raw punk band or super fast or super heavy, groove was our approach to the songwriting.

Logan Montana: I would say that, yeah. Soul music is what we were listening to at the time. Henry more so. Henry’s a musician and composer, not just a vocalist. I know sometimes it just seems like it’s all “oh! baby! yeah! oh! baby! kill myself!” But he plays a huge part in composing the actual music itself—a lot of it comes from Henry.

Emil Bognar Nasdor: Henry is one of the best composers from that crew that came up through the 2000s. I think he’s a very brilliant writer in whatever instrument you put him on. I hold him in a very high regard as a composer and player.

Henry Wood: All of us listened to a lot of shit that wasn’t just punk.

Emil Bognar Nasdor: I studied percussion at the Collective School of Music. It took me four years to do a two-year program—I was very, very immersed. I got really into Brazilian percussion, African percussion. I was very active in all these bands in that scene, but I was also doing way other shit at the same time in that era. I was doing experimental evening-length theater pieces. That rig, let’s just call it the Stay Home!! rig, was developed from Latin music studies. Those rhythms were very intentional. It wasn’t just like, “Oh, I’m gonna bleep-blop around these drums”—I studied vocabularies and different styles. I knew I was bringing a different flavor of rhythm to this soul, high on punk, Western guitar music stuff.

Henry Wood: I think we were trying to make something different from what we had done before. I don’t have any memory of being like, “Let’s make a soul record.” But it’s hard to say how the music you’re listening is going to affect how you’re writing.

Max Quinn: When people hear our band and kind of project our thoughts of what we’re going for. We sometimes get pigeonholed as a garage rock band, and we like to nip that in the bud.

Henry Wood: We all came out of punk. I get kind of angry when people call us garage rock. We have no fucking connection to that shit. I think what’s telling about it is that it’s hard to describe us by naming two bands. The classic review formula. “It sounds like this band and this band.” I don’t think we’ve ever said “let’s make a song like _____.” Everything we’ve ever done, good or bad, is the thing that comes out. That’s it. It’s an amalgamation of all of us, nothing more and nothing less.

After finishing and hashing out the songs of Stay Home!! in a studio setting and committing those performances to record, Hank Wood and the Hammerheads would gradually alter the sound of those songs through extensive touring.

Emil Bognar Nasdor: It was like so many records that I was part of during that time and before: You would write the record, record it, and then play it out, and it would always get better, like, a year into playing it out.

Henry Wood: We did a big Euro tour.

Max Quinn: Between Stay Home!! and the self-titled, we did a bunch of little tours. Behavior-wise, we were getting even crazier in a different way. The Euro tour was interesting because we had to play 45-minute sets. Having Emil in the operation, we learned how to be kind of an airtight operation.

Henry Wood: There’s a video of us playing in France and we play…“Dog.” What is that actually called…“I’m livin’ in a concrete pit!” Oh: “Shook and Hungry.”

Max Quinn: We don’t even remember the names of our own songs.

Henry Wood: We got to playing that so psychotic.

Max Quinn: It became a game to see how fast we could go. Emil would set the tempo to play that crazy syncopated cowbell thing.

Emil Bognar Nasdor: My hands cramped up. It was very brute force style. I would really lay into the instruments. I remember trying to push that tempo as much as we could to see how twisted we could get it. And then a few of the other songs, like opening up solo sections live and having more psychedelic, tripped out, longer solos.

Forest Byrd Looker: For the first record, I had that old Farfisa. It has the wax wound transistors in it and they would go out of tune all the time. When we started touring, the guys were like, “We're not lifting the fucking Farfisa.”

Emil Bognar Nasdor: I’d gotten the rig down to one main stand where I kept the few main drums and cowbell and tambourine. It became something I could pick up and throw in the back of the van where it wasn’t like 40 fucking cowbells. I do remember the tambourine rattling around in the back and people losing their minds. I’d kind of get off on it. “Oh, tambo’s making some noise back there!”

Logan Montana: We got better at touring but there were a lot of growing pains, a lot of hard lessons. It was a tough one, but we got through it. No fistfights or anything, except…well no, me and Henry on that last night. Not over anything. It was cute. I think I pushed him while he was peeing on the street, and he hit his head on the wall by accident, and he just punched me in the face. And then we laughed.

Henry Wood: That tour was sick. We were playing almost every song we had. We got really, really tight. Hammerheads is always really fun to play, and everyone is such a good musician, and we’ve been doing it for a really long time. I feel like we’d just fall into the pocket, and that’s not always the case, but there was something about that era of us where we got really, really tight.

Max Quinn: It’s not very punk to talk about our craft, but we got really fucking good at playing.

Emil Bognar Nasdor: When we would really hit into the, for lack of a better term, the flow state—that’s the power of live music when everyone harmonizes into that energy and is really showing up. It was incredibly powerful with six people. It felt amazing when that would all line up. That part’s a very fond memory. The shit was unstoppable. It felt insane. It was just a force.

Following Stay Home!! and the subsequent tours, Emil decided to depart Hank Wood and the Hammerheads.

Emil Bognar Nasdor: I walked away from a bunch of bands at the same time.

Logan Montana: There was no concrete reason, you know? He was getting really into recording music himself. There was no specific flare-up, he was just exploring his own life. There was no sit down or talk, it just kind of organically happened.

Henry Wood: I think he just wanted to focus on other things.

Max Quinn: Emil is a pretty singularly driven person with whatever he’s working on. Especially after the time of making Stay Home!! into whatever we were doing next, this band was demanding a lot more time.

Emil Bognar Nasdor: I really wanted to keep expanding the edges of what you can do with music, and I felt that the group was kind of content to continue doing the stuff they were doing. That was really not attractive to me.

Henry Wood: We love Emil. He’s doing a lot of really cool shit right now. It took a little bit of adjusting to kind of figure out how we wanted to play without him, but at this point, it feels so natural without Emil. Nothing happened.

Max Quinn: We talked for a little while about trying to fill that role and having someone else do what Emil did, and I think we made the right decision. We have a core group of us that have been doing this together; we have this whole dynamic.

Emil Bognar Nasdor: I always wanted to change things every night. I was like, “Yo, what if we open up this section? What if we do this?” And people were like, “Yo, what we’re doing works, why do you want to keep fucking with it?” My creative energy is just very different. Different goals. A lot of the time I want to get to a place with creativity where it’s hard for me to understand what’s happening. I think that’s where the really wild stuff starts to blossom.

Looking back on Stay Home!!, the band considers the album’s legacy.

Forrest Byrd Looker: In New York, it'll probably be: “Remember these fucking assholes?” I think the legacy of that record is gonna be a cautionary tale or something. At its core it's really a piece about depression and isolation—when you're fucked up and no one wants to be around you. The door's locked and your girl leaves. I don't even think we meant for it to be that way, but at the end of the day, all the songs are about regret. Like, “Fuck man, I fucked up,” and then the next song is, “I’m not gonna fix it.”

Logan Montana: The self-titled album is by far my favorite, and I would say that’s kind of the general consensus in the band. We took what we did on the first record and second record, figured out what worked and didn't work on both, and very organically, that's where the self-titled went.

Henry Wood: I think Stay Home!! was young us being experimental and willing to try new shit, whether it worked or not. The self-titled was that, but one step further. Maybe it’s more confident. It feels like we know ourselves better in the self-titled than in Stay Home!!. Stay Home!! is thought out, but it has that chaotic messiness that Go Home! does. The self-titled, we’re chaotic and messy sounding, but it’s like [speaks with cartoonishly assertive enthusiasm] “we are chaotic and messy!”

Does the future hold another Hank Wood and the Hammerheads album?

Kevin Manion: We all kind of agreed that we’ll write at least one more LP and then call it quits.

Logan Montana: I’d love to.

Max Quinn: I don’t know. We’d all like to. We’re in a very zen place as a band right now.

Henry Wood: Yeah, it’s trickier now because Forrest lives in Texas and Kevin lives in Philly and we’re all older. But I wouldn’t count it out.

Max Quinn: We have riffs floating around.

Henry Wood: If we get bored enough.

see/saw is a reader-supported publication. If you enjoyed this article, please consider a paid subscription to support this independent punk journalism operation.