chubby and the gang on closing a trilogy + the power of unions

Following his new album And Then There Was..., see/saw presents two conversations with the uncompromising Chubby Charles

In spring of 2021, Pitchfork Union was very close to going on strike. In the days before Condé Nast’s lawyers and the union’s team reached an agreement on a contract, paperwork was being filled out and we were fully prepared to picket. As part of that whole thing, we decided to put together a strike zine. Everybody contributed something, an essay or interview or review, mostly with a focus on workers’ rights. I interviewed Charlie Manning Walker, aka Chubby Charles of the ripping UK Oi! greats Chubby and the Gang. He was a contemporary punk voice shouting about worker solidarity—an active member of an electricians’ union who works on film sets.

Months earlier, the band had released “Union Dues,” a song about the very specific nature of going on strike. He sang-shouted about a company making “promises of pie in the sky.” He specifically railed against companies bargaining in bad faith, and the Gang definitely don’t fuck with scabs. Sarah Jaffe’s book Work Won’t Love You Back seemed to be invoked when Manning barked “don’t come round here lookin’ for love, we’ll show you where to go.” Speaking to him at the time was invigorating. Hearing someone with anger in his voice, talking about how crucial union contracts while scoffing at hollow boardroom talk, was a rare instance of solidarity from the music world outside the realm of media.

It was definitely a positive that we got the contract and didn’t have to run the strike zine at the time, but it’s a piece I’ve reflected on regularly. It’s been over three years and a lot has changed in both Charlie’s life and my own. We’re both still pushing our wares, but things feel different. His latest album And Then There Was… arrived in September, the band’s best record since Speed Kills. It opens with a bang. Created in a studio with Jonah Falco and James Atkinson, it’s a record that merits a deeper consideration here at the end of the year. It sounds major, both reminiscent of the best Gang songs while also sounding more mature. It completes a trilogy of albums, giving the closing bruised piano ballad “Cocaine Sunday” a true heft.

Listening to the album, I thought a lot about our earlier conversation. His politics have always aligned pretty tightly with my own, and I’ve always admired his work. There’s an ambitiousness to this newest album, which I think can sometimes get knocked in the punk world. That’s silly, though, as there’s plenty of room in punk for ambition. The journey from the punchy immediacy of Speed Kills to a more patient work like And Then There Was… tracks “To Fade Away” and “Cocaine Sunday” should be celebrated. Presented here are conversations from different points in the Chubby Charles story—one from October just after the new album’s release & the 2021 pre-see/saw chat about workers’ rights.

October 7, 2024

Can you tell me a bit about how the process of making this album compared to the previous two?

It was more similar to Speed Kills in a sense. I was just talking about this earlier, actually, like the whole thing has been happening through COVID times essentially, and this was the first one on the sort of on the other side of COVID. So like with Speed Kills, I wrote all that in my room, kind of like, “I don’t know whether I should do it at all,” and Jonah helped me facilitate that into reality. Once the band got a bit of attention, once you've got eyes on you and stuff like that, it's much easier to do stuff. Things went back to square one a little bit and then so it was like sort of just starting again, really, but I think there was like a bit of a point to prove, you know what I’m saying?

But in terms of like the actual making of it, what we usually do with Chubby and the Gang is i'll go in to a studio in London take a bit of time demoing some stuff out and then then I’ll start presenting it to like the band or whoever's going to be involved in recording process. So really, the difference on this one was more to do with everything after the writing had been done, the facilitating stuff rather than necessarily the writing process.

Were there any moments working on this record where you surprised yourself? I’m thinking in particular of how your voice comes through on “Cocaine Sunday” as a difference between the new one and previous performances.

I mean, a lot of that's probably confidence, you know? I've never been a singer, and I've always been someone that writes songs but i'm not a good singer. But as time went on, I sort of started becoming more like, “Yeah, no, I could do that.” I sort of started believing in myself a bit more, because it's one thing expressing yourself and there's another thing being like, “Oh, I could do this.” Do you know what I'm trying to get at? So it was more just being able to be like: I've done two LPs where I've sung on it and people sort like were into both of them, so I must be doing something right. So why not just try it?

Was this one just you and Jonah recording?

It was me, Jonah, and James Atkinson, who owns the studio that we recorded at. I mean those two guys are really close friends of mine, so like Atko—we call him Atko, James Atkinson—and Jonah, those two guys are a rare combination of good taste, talent, and ability. They’re two unicorns, basically. Having them in the studio is great because I feel like musicians often get a little bit up their own bums. They love the smell of their own shit. So having someone there to be like, “This is not, this ain't the one, mate.” Or flipside, sometimes I would psych myself out about stuff and be like, “Man, this ain't working. I want it to sound like this, but it's not.” They'd be like, “No, no, no. You're almost there. One more time.” And then I'd get it and I'll be like, “Man it wasn't for you being here this song would have been scrapped.” So having them there, it's hard to fucking lose with them two in the room. They’re fantastic.

After speaking with him earlier this year, Jonah seems to me like the kind of producer who’s more of a collaborator in a creative sense than just someone behind the boards or whatever.

Yeah, he definitely is. This word has a negative connotation but he's like an enabler. He’s like, “Yeah, you can do it.” A lot of people will come to him and be like, “I don’t know, man, I'm not sure.” He's like, “No, no, no, look, let me,” and he helps you get there. Like, there's a couple of times on a record where I knew what I wanted to happen, but I didn't know how to make that happen. So I was like, “I don't know what this instrument is, but I want it on this song, and I don't know how to make this happen.” And then he'd be like, “Oh, that, that's a fucking…” you know, Mellotron or something. I’d be like, “Ohhh!” So yeah like he's fantastic like that. If you're someone that's new to music or want to expand into territories that you don't really get—like I was—he’s absolutely fantastic for shit like that.

I talked to Jonah about the handclaps on “Uxbridge Road” earlier this year. Do you feel like the elevating pop touches were his influence?

Well, I was the big pusher on the pop thing, but in terms of elevating it, he certainly does that for sure. I went into Chubby and the Gang because at the time, in the scene that I was in, I felt like there was like a sort of Chiswick Records hole which needed to be filled. I just wanted to do everything that was on Chiswick like Motördamn, Johnny Moped, and things like that. I was like, this is the stuff that I'm listening to at the time—well that I’m still listening to—and I wanted to make it where it's palatable enough where a 10 year old can say, “I like this.”

But he was certainly the guy that helped me get there. I haven't got the vocal chops to do a proper good oohs and aahs, and he does. That is something that helps, having him there. “All Along the Uxbridge Road,” the harmonica was because I had a harmonica in my car. At the time, I was driving a taxi, and we had this bridge and I was like it's empty, it's not working, it needs something. He was talking about guitar so I was like, “Fucking guitars, every song is a guitar,” so I went into my car, found the fucking harmonica that was in the right key, and I was like, “If this isn't a fucking sign.” Went back in there and just fucking did it. I feel like that kind of set the trend within the band to add different stuff, like, “Hell, the last song had a harmonica on it!”

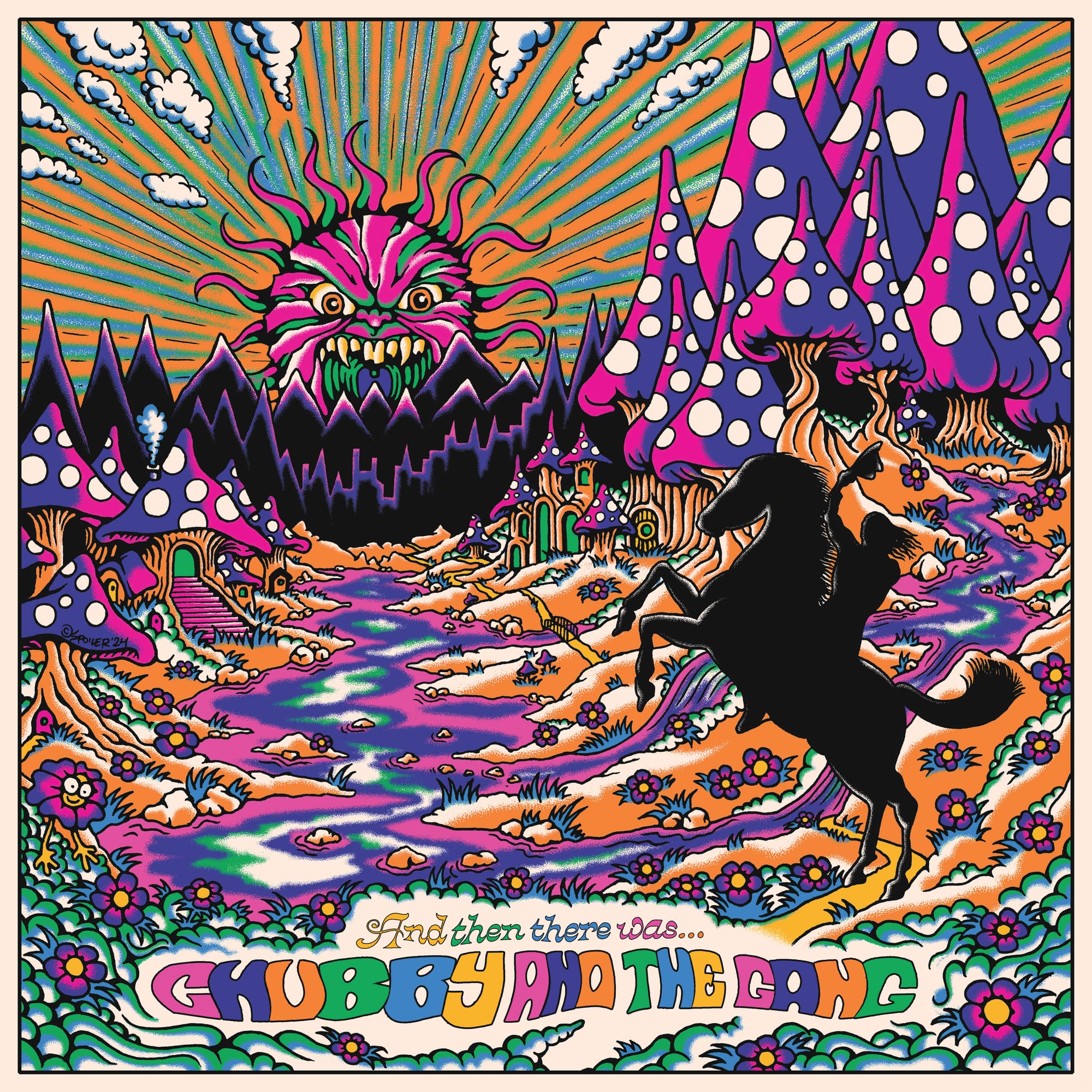

The album cover this time has a different aesthetic than the previous two. I’m wondering what your thought process was this time?

From the start—from the very first one—I wanted to do a trilogy. A sort of journey. This one is the final part of that trilogy, so I wanted to make it feel a bit more like an exit, you know? The guy going off into the distance, the sort of long winding roads, the fact that he's like alone on it. I wanted to keep it psychedelic, like the walls are melting, but this is kind of the thing. And hence “Cocaine Sunday” being at the end of it as well. I'm not saying that this is the last record Chubby and the Gang will do, but I wanted to make it the end of a trilogy. There's more purple, like the end of the night type shit. It’s an exit; closing time.

What do you get out of Chubby and the Gang that you don’t from other bands you’re in? Is it primarily that it’s an outlet for songwriting?

I'm big into songwriting. I do it not necessarily with any intention in the literal sense. It's a hobby which results in an album being made. You know what I'm saying? I mean, if I could show you my fucking phone, I have these videos that I record myself playing guitar riffs. It's like, “Chubby and the Gang ideas” and underneath it's like 300 videos. I'll just sit there and sort of write and write and write and then if it sticks, if I like it, I’ll use it. I tend to be quite hard on myself with writing where I don't want to be the type of person that's like, “I like this, so everyone must like it.” Musicians have a tendency to feel like they have the highest touch. So I just write and write and write. I had to fucking cut two of the tracks on the vinyl of this record because of it being so long, but they're on the download link. We end up just coming up with tracks and tracks and tracks and tracks. The challenge is cutting them out. If anyone’s reading this and wants a song written, I’ll do it for a six-pack of beer.

How’s electrician work, you still doing it?

Yeah, yeah. It’s my one day off this week. I’ve been doing it because I kind of want to separate myself from the reaction of the record being released. Maybe that’s an anxious thing, I’m not sure, but I was like, “I’ll just go to work.”

There’s a lot of noise on the internet, sometimes it’s best not to deal with it.

Yeah, it‘s a lot of attention that makes me get a little bit shy. I’m not really sure how to phrase it because it’s more avoidance than anything. I’m just anxious about how the record’s gonna be received and I’m in denial about that.

I wanted to thank you for doing that unpublished strike zine interview a couple years back. At the time, it meant a lot to me as a show of solidarity; it also deepened how much I wanted to do stuff like that just for myself after Pitchfork. I also still think about the necessity of unions and get genuinely angry when corporations or politicians spout some line about how unions would make a worker’s life worse somehow.

I’ve never met a person who said something like that earnestly. There’s always something behind what they say. I can’t remember what company, it might have been Delta, but they were offering like “if you don’t join the union, you’d have the money for a Playstation” or something like that. Like oh, it’s like that to them.

My union contract, for a couple years there, was life-changing in some ways.

There’s obviously the American election coming up, and we’ve just had an election over here. We had a conservative government for like 15 years or something, and the opposing party historically was created by trade unions. Now they’re in, they had this guy who’s tried to remove them from the trade union history of the party and become, in his eyes I guess, more “moderate” or whatever you want to call it. He’s showing his true colors a little bit and I think more and more people are becoming disillusioned with the mainstream two-party system. It’s like you’re asking me what bollock I want to be kicked in. People will be turning more and more to trade unions. I’m not trying to talk badly about democracy, but it’s difficult to really believe in something when you have two options and you don’t want either.

There was something powerful for me about that chat we had because I think sometimes the rhetoric feels like it only exists online. Like to speak the words out loud felt meaningful.

I’m trying to get more and more involved with the musicians union. I’ve been talking to my friend Tom, he’s a player in that world. In my opinion, it is actually very simple: People are exploited for their labor and that needs to stop. Whether that’s a musician or a bricklayer or, I don’t know, a fucking astronaut. At the end of the day, you need to have some sort of voice within your own workplace, and I think musicians have a really bad habit of having surface level politics. It can be as simple as, “I am learning less because of this tax.” That’s what I tried to do with some of the Chubby and the Gang lyrics. You can talk about a politician in a Senate somewhere and be like “what a bastard,” but I’d like to talk about the effects of what that law does when it gets down to the people, you know? Now I haven’t got money in my wallet. I can’t go and do what I wanted to do. I think that’s political as well.

April 28, 2021

Could you tell me a little bit about your experience being in a union?

The thing about my job is that everyone is self-employed. People hire me through word of mouth within the union. If a production is trying to undercut the union rate or if they’re trying to force unsafe working conditions—there’s a whole list of reasons why a production might try to do something silly—we get told about that by the union and we have to turn down the job. My job is a trade. You’re a qualified electrician, but you’re doing it in a creative capacity. I’m presented with productions all the time who are like, “Could you just work the extra two hours? We don’t have the money to pay you for that, but it would really mean a lot to us because it’s a passion project.” And I’m like, “No, it’s your passion project. I have to put bread on the table. No one’s gonna put me up for an Oscar any time soon, I’ll put it like that. You’re gonna get a pat on the back and a fuckin’ medal, and I’m gonna get fuck all.”

One of the fuckin’ things that really fucks me off about the creative industry is that you have to fuckin’ flagellate yourself to get somewhere. I don’t understand why this culture is in a place where people are like, “Oh yeah you have to starve for your art.” I think it’s insane. For me, it creates a really toxic environment where people are iced out. They’ll offer these low paid internships and unpaid internships in creative industries to stop people from lower income backgrounds from having access to a job. Whether that’s intentional or not, I have no fuckin’ idea, but if you create a system where you have to work six months to a year with no to little pay, immediately you’re targeting women and people of color and people of working backgrounds, because a lot of people can’t afford to do six months to a year unpaid. If you’ve got kids to look after, and all of a sudden your dream job pops up, you’re like “wow amazing,” but it’s six months to a year unpaid. How the fuck you gonna do it? You can’t.

Yeah that’s part of Pitchfork Union’s fight. People are brought into these publications at entry-level positions with the promise of prestige, opportunities, and how it looks on a resume, but it doesn’t pay a New York City living wage. In order to do this work, you have to come from money or be willing to amass serious debt.

It’s a fuckin’ joke, because a lot of companies will on one hand try and peddle some inclusivity line as a publicity thing and then turn around and make people work for nothing. You can’t have one and not the other. How can you tell me you’re inclusive if you don’t pay people? It’s betrayal. If you enjoy what someone is writing and you want to publish it, or if you appreciate someone’s work and there is money to be made, then that money should be passed around.

Did you write “Union Dues” to empower union workers in labor fights?

Absolutely, 100 percent. The thing that really makes me proud of our trade union is that we’re willing to fight for what we believe in, for our rights, and for each other. A lot of political songs in 2021 are very apologetic, almost. There’s this tone of, “Could we please?” Fuck that! No “please.” We need to be paid a living wage. People need to be paid a proper wage in 2021, and that is it. And if you can’t meet us on that, then fuckin’ be prepared for strikes, end of story! I’m sorry, but I’m not going to apologize for being left wing, ever. This is what I believe.

What would you encourage people outside a union like ours to do in order to show solidarity with workers on strike?

It’s always good to help raise money. If you’re a musician and you’ve got friends who are musicians or journalists going on strike, you can do gigs to raise money. I think it’s about time that we, as the music community, start banding together, because there’s a really clear us and them. I think it’s time to band together across…I was gonna say “party lines,” but that’s not what I mean. I think it’s time to stop thinking about the music world as “departments” and more time to think about “who’s standing at the bottom of the hill and constantly getting shit rolled down at them?” We should have solidarity amongst that level of people because we’ll become a much more powerful unit.

Musicians in 2021 are really dancing around certain subjects and they’re getting up on stage and being like, “Oh man, isn’t greed bad? Yeah, fuck, greed is bad, yeah. Anyway this song’s about greed.” Unless we get past that initial very obvious fucking criticism of the world, we’re not gonna get into the specifics and therefore we’re not going to change it. Maybe I’m sounding like a dickhead here, but if you get on stage and say that, it’s like yeah, I know that, bro. I’ve known that for a long time because I’ve worked a lot of shit jobs.

It’s very easy to say “this is what I believe” and it’s a whole other thing to do something actionable.

I think a lot of people get scared. That’s a tool—a tactic that’s like, “if I speak up I might not see another job.” That’s where it falls down to that solidarity bit. They can’t fire us all, that’s why we need to stand together, and that’s why it’s important that people don’t scab. For me personally, I wouldn’t even sit at the same table as a scab. If someone has scabbed in my line of work, I won’t work with them again and I won’t be on the same set with them again. That may sound tough and that may sound harsh, but if your only weapon in a fight is to withdraw your labor and someone blunts your sword for their own gain, then you have to realize the seriousness of that situation. It’s not fair to everyone around you, and you put everyone in that situation for your own gain, and I don’t fuck with people like that.

I love that there’s a line about scabs in “Union Dues.” A lot is really clearly stated.

That’s what I mean! All this music in 2021 is steeped in metaphor. I want you to listen to “Union Dues,” yeah, and I want it so even if you’re not trying to look for the meaning of the song, you cannot deny what this is about: “Please do not scab.” I didn’t want people to just skim over this. This is the topic of this song, I feel strongly about it, and I want you to feel strongly about it too. I’m gettin’ all heated, mate, you got me all worked up!

Hey likewise, this conversation has been empowering.

But this is what I mean, you should feel empowered! We are the people. We are the numbers. We have power in our numbers, and people are fucking convinced that we don’t, but we do. We need to clock that and realize it. We’re the ones that create the music, we’re the ones that create the articles, and fuck it, we should be paid. That’s a full stop. End of story.

see/saw is a reader-supported publication. If you enjoyed this article, please consider a subscription to support this independent punk journalism operation.