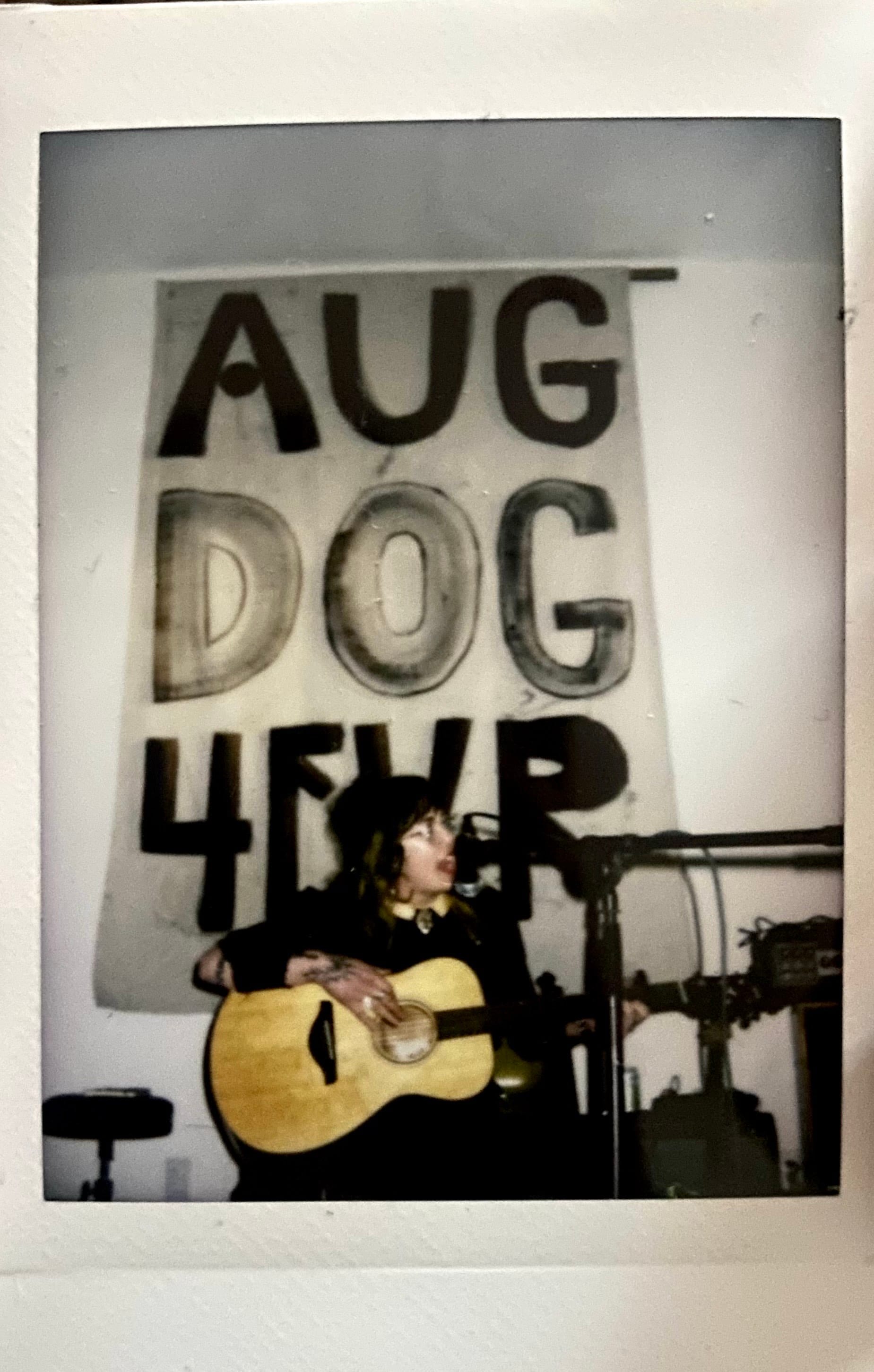

caitlin angelica and the act of grieving by singing really loud

The screamer and songwriter behind Makin’ Out, one of Minneapolis’ best punk bands, doesn’t want the worst day of her life to define her forever.

Caitlin Angelica’s room in South Minneapolis is a palpably safe space. The walls are mustard yellow, strewn with string lights, and covered in mementos. There are multiple comfortable spots to sit and an acoustic guitar in the corner. Her big and very sweet dog Oakley is snoring major over on the bed. “She’s such a sad baby,” Caitlin says with clear affection. “She’s like, ‘nobody loves me. I went on an hour-long walk earlier.’” It’s an easy place to be comfortable and sip a drink and talk about big and heavy shit. There are records and tapes, show flyers, portraits of Patti Smith, country music novelties, and of course, works of art created in tribute to her late partner August Golden.

August was shot and killed at Nudieland—the Minneapolis punk house where he lived—on August 11, 2023. It was a Texture Freq tape release show; familiar faces from the city’s best punk bands were in attendance. Caitlin was standing right next to August when it happened. Of course she was there. She’d been going to punk shows in Minneapolis since she was a teenager. She’s lived in multiple punk houses over the years. And she was deeply in love with August. Of course she was there.

In the days and months before this life-altering loss, Caitlin had been writing songs and performing them at the top of her lungs. Before an impossibly more brutal impasse, she was shout-singing about loss and sobriety and tumult. Hollering melodically, it turns out, is physically therapeutic. She was rooted on by August, her biggest fan—a cute boy in a great band. Following a solo demo, many of those songs made their way onto Living in a Glass House, the phenomenal debut album from her country-tinged pop punk four-piece Makin’ Out.

Caitlin screams in the hardcore band Step Sister, but in Makin’ Out, her voice is a completely different instrument. It’s vulnerable and elastic. Cracks and quakes in her delivery aren’t about trepidation, but power—the inherent product of singing (her words) “horribly fucked up sad” lyrics as loud as fucking possible. “I’d do anything to have you near/hold your hand while you sip a beer/my knees are weak from that smile of yours/long dark hair, cut with no remorse,” she sings on “Fill the Wells.”

In early 2024, the band opened for the Marked Men at a sold out Minneapolis show. It was just months after Nudieland, and between songs, Caitlin talked about August. In the record’s liner notes, there are easter eggs in tribute to him—images culled from his possessions and his father’s old journalism job archives. Holding a copy, she points to an illustration pulled from an encyclopedia of stage magic: “I think she’s giving widow.”

In Minneapolis punk world, Caitlin is a public figure. She’s in multiple good bands, works at the good spots, shows up to the good shows, and is instantly recognizable in a crowd. Two days before our chat, she was laying low at the TAKAAT warehouse show. Sometimes you don’t want to talk to an enthusiastic circle of homies but would very much enjoy having your senses inundated by a wildly powerful live show at the new warehouse spot (name still pending, I think).

Just before her album’s release and a U.S. tour, this person who’s at all the shows had her picture published via national news outlets. She appeared in the courtroom and read a statement at the sentencing hearing for August’s killer Dominic Burris. During a press conference, which was attended by many familiar faces from the greater scene, she responded to a question wondering about the state of the Minneapolis punk community.

“That community is standing in this room with you right now. It happened at a punk show. I’ve been going to punk shows since I was 14 with my mom, and as I said in my statement in the courtroom and as you can see here today with the presence of the people around you, it’s still there,” she said. “I went to a show the week after it happened. To the hour. There’s a big change, and we all have a lot of trauma—which we already all did. We don’t have August, and it would I guess be naive to say that there hasn’t been strife within the community, as any communities who are experiencing stress have. But we are doing exactly what we were doing before with maybe a slightly different perspective on the world.”

When I asked where she’d be most comfortable to hang out for this interview, she suggested her house. About two hours after I drove away, I saw her on the sidewalk outside the Citric Dummies, Yambag, Surrogates, and Buio Omega show at 7th Street Entry.

First question: How are you doing these days?

I'm good. I’m doing pretty good today. I feel like life, the last couple months, has been incredibly chaotic and now I’m finally getting back into the swing of some sort of semblance of a routine.

Yeah, this period around the album’s release looked incredibly busy and hectic just on social media alone.

Yeah, so the album came out like a month ago, which is crazy. In the weeks leading up to the album coming out, there was a trial…well not a trial, but hearings for the murder of August. And so that was at the end of March. I did that. We all read our impact statements and had that day, which was really intense. I played two shows that week—a solo show and a show with Makin’ Out—and then a week and a half later, I went down to New Orleans to go to my friend’s memorial. I was there for four days and then I came home and had five days before tour.

In those five days, it was a show with Step Sister and then a show with Makin’ Out as our tour kickoff. I knew what I wanted the insert of the record to be. I had it planned out, mapped out in my head, but I hadn't done it yet. So I had to make that and also have practices. Then I went on tour for nine days and came home. The morning that I came home, I had friends in town who had gotten here the night before that were visiting for May Day, which was four or five days after I got home. So I feel like people left town like a couple of weeks ago now, but I still just feel a little like, wow.

It feels like a year and a half of pretty nonstop motion just because of trips and memorials and recording and tours with other bands and playing shows in other places. The hearing stuff was very sporadic. I would get calls, like there would be a hearing like three days from then when it was supposed to be a week. It was just so up in the air all the time.

Are you comfortable talking about the hearings? That’s got to take an enormous amount of your energy and emotional space. Like, how is the comedown from something like this for you? Are you by yourself? Are you with your friends?

I mean, you can definitely ask me any questions about them. I feel like I’m very open about them. I think grief has a tendency to create these anticipatory feelings. There wasn’t a trial, right? The defendants took plea deals, and so in November we did a sentencing hearing, and at the end of March, we did a sentencing hearing. I knew generally what both were gonna look like, but obviously I’d never been in a room with…well I had been in a room with them, but I’d never been in a room where I would read an impact statement to a judge in front of the person who killed August. It was a lot. It was the single most difficult thing that I’ve done intentionally with my time. I could have chosen to not read a statement or not be a part of it, and I’m not saying that I’m holier than thou because I chose that.

I do think that it was important for me to have this feeling of some sort of control in it where I'm telling my narrative to the judge in front of the defendants, in front of the room filled with people from my community and friends and family and loved ones. And to be like, “I actually don't believe in the carceral system, I don't believe in punitive justice. I don't believe in people going to prison in general or anything about it because I don’t think it brings me closure, I don’t think it does anything to actually change the systemic violence that we experienced.” I could go on forever about it.

It feels like because these things were so sandwiched in between me leaving town and shows and all these things that were good, I think it kept me going, it definitely is like just a month and some change later, I’m processing the fact that I did that. We chose to do a press conference so the press didn’t jump on us when we were leaving the courtroom. That was all over the news, all over Instagram. I still get random notifications from it. It just feels bizarre. It’s like an unreality where you’re like, “Why?” People always talk about it in this way where [an event] feels like re-traumatizing, and it’s more like quote-unquote “re-traumatizing.” I’m just traumatized. We’re all traumatized, and the wound is just kind of open generally. I can function with that there, and I’m OK, but I’m inundated with this stuff all the time.

The hearings and stuff and the court side of it wasn’t so much re-traumatizing as much as it threw me out of my body completely, you know? I’m glad I did it because Auggie...August’s family isn’t here. I think ultimately I did it because I can’t see any part of this process being, for a lack of better words, rehabilitative for the kids that did it other than hearing from the people that were like the most impacted that do have a certain amount of empathy and grace for the system that actually put those kids there in the first place—that, in my mind, put guns in their hands. It’s not black and white. It’s very nuanced and complex. But yeah, to answer your question, the lead up and come down has been very bizarre. I just got a call from one of the people earlier. There’s another thing, and it’s tomorrow.

It’s tomorrow?

But I’m deciding...I shouldn’t talk about it very much. I’m deciding if I’m going to engage with it, because at this point...it’s not about moving on, but it’s really disruptive. I know I have a choice, but I don’t feel like I have a choice physically in my whole being. Not just with the thing tomorrow, but in general engaging with this. Yeah. I just want it to be done. [laughs] That’s really the long and short of it.

When you say you want it to be done, do you specifically mean the hearings and court appearances and bureaucratic stuff?

Definitely. I feel like for such a long time, like working in cafes in the city and being around for as long as I have, I wouldn’t say I’m a very public…well I mean, I think now I’m a very public-facing person, but I’ve lived here for 16 years, you know? So I feel like I know everyone, and I feel like everyone knows me. I’m proud of myself and my community for being able to use this thing that is really awful to change and maybe shift the perspective of what a victim can look like and can be—to maybe have a tiny bit of reclamation of our own powerlessness, you know? And it’s like fucked up. It hurts. It’s really awful, but also I’m glad that I did it. I just want that part to be done so I can…not move on, like I said, but just do my thing. [laughs] Just do the other things I like to do like make art and go to shows and play music and hang out with my friends.

How long had the Makin’ Out songs been around by the time you recorded them? Can you tell me a bit about where this specific side of your songwriting got started?

I started playing guitar in 2021. I tried many times over my lifespan to play guitar. I took piano lessons for a while as a kid and guitar lessons as a kid. I took piano lessons and guitar lessons as an adult at different points. It just never stuck. I started playing guitar in August 2021, and I had just hit a year of no drinking. I think at this point in my life, I was 26, and I couldn't ever focus on anything before other than art that I would make. A year into sobriety, I was like, Oh, I can create new neural pathways and work on things that were otherwise so irritating for me. I’d gotten an ADHD diagnosis and medication and stuff like eight months before. I started playing and it was so irritating and hard.

August, we had just started dating a few months before that. He’d always be like, “You’re not good at something right when you started? That’s so crazy.” It was definitely this thing, because we were dating long distance between New Orleans and Minneapolis, that I was like “He’s either here or I’m there, or we have these month or two spaces in between.” I just felt way more settled with myself and my being, so I could be at home and work on stuff. I don’t know what switched. I just got hyperfixated on it. My friend—who passed away a couple years ago—10 years ago he gave me this classical acoustic from the Seward Cafe free box and I had never really played it. So I just started strumming chords and trying to sing at the same time, and God bless my old roommates in my old house because it was so brutal.

It’s crazy, too, because I’ve always sang in my life. I’ve been writing songs in Step Sister for almost seven years now. I’ve always written stupid little songs for myself, but I’ve never been able to sing in the way that I do now until a few years ago. I think it was a confidence thing. Really, it’s a muscle, practicing it, and having a lot of perspective shift in my life and honestly not giving a fuck what people think of me in a lot of ways.

So I just really started working at it and started sending my little songs to August and showing friends. In spring 2022, I remember I had COVID after we all went and saw Jawbreaker at the Fillmore. It’s a really bad place to see a show. I got COVID and I remember playing guitar in my room and just kind of losing my mind because I had it for a week and it was before May Day. It was right before August moved here because he moved here like right before May Day 2022. I sat down and wrote my first real song. It’s still a song I play solo today and it’s not on the record, but I remember August being like, “Wait a minute, why don’t you sing like that all the time?” And I was like, “I do, but just not in front of people.” I was like, “I’m impressing this cute boy that I’m in love with from far away.” It just felt really good. It’s like every time I write a song, I’m like, “I can take over the world!” [laughs]

The first time I saw Makin’ Out live, you were opening up about August and the shooting between songs. Doing that in Minneapolis is probably a pretty specific feeling because you knew so many people in the room, but do you feel like you can do that when you’re on the road regardless of who’s in the room?

I thought about this a lot actually leading up to tour, like, hmm, how am gonna navigate this? Because I have played on both coasts and in New Orleans multiple times, solo at least, since August was killed. So many of my songs before he was killed were about grief and specific heartache stuff, but then also big enough that I could just roll with it and not have to go dive into it. But obviously, all of the songs that I’ve written since he died are about grief, about him, but also there’s specific things in them that are about very specific moments or breakthroughs or what’s physically going on around me.

So I think very early on after he was killed, I would give every piece of context. I just generally talk a lot—sometimes it’s to a fault how vulnerable I am. Because sometimes I’m like, “I don’t need to be giving people all of my energy about this.” Sometimes it’s not received well, you know? I don’t feel ashamed or embarrassed when that happens. Sometimes people are not ready to receive something, but in a room when I’m on stage, I have the microphone, I’m doing it, and I am going to give context for songs.

I think I do it in a less detail-oriented way than I did when he first was killed, because every time I stepped on stage, it felt like I was memorializing him. Still, to a certain extent, every time I step on stage, I’m memorializing him or I’m memorializing anyone that’s my friends. It’s the way that I am able to get through life is by playing music and making art. This part of it happens to be very public.

And I think it’s important. I love hearing about the context of people’s songs. I really love hardcore and punk as much as the next guy, like so much, and I love not being able to hear what the fuck people are saying, but I do love to know what people are singing about and I love lyricism. Being here, it’s very different. This isn’t even about one specific person, but I can see that people get squeamish or have a hard time because we are in Minneapolis where it happened. Sometimes I’m in a room and like half of the room will be people that were there at Nudieland. And sometimes I draw it back if it feels a certain way, and I don’t need to even have it be so detailed, because they know, you know?

And then when I go to other places on tour, we have two setlists, and we were going to do one but I kept messing up one of our songs. So we decided to not play it, but this other song is “Uncertainty,” which is the punk song I wrote for the Marked Men show. So we had this specific setlist: “Bear the Weight” and then “Suspend Me in Time” and then “Glass House,” which is the title track of the album. I had a script essentially where I’d be like, “So this is the title track of our record, yada yada. It’s in the back. Buy it if you want, whatever.” Play the song.

And it’s like, “That song is about alcoholism. I started writing it before August was killed. I was actually supposed to play it the night before he was killed because he was like, ‘You should play it at the solo show.’ That was my second solo set ever. Then I didn’t play it because I didn’t write it on my fucking setlist. And so it felt really sad because I didn't play it. But he was like, ‘It’s not done. Just play it.’ Forgot.” We had “Fill the Wells” be the fourth song, which is obviously a very intense song that’s very directly about gun violence and partner loss and how if you experienced neither/nor, you will never understand.

I don’t know what the purpose of that...I don’t know why I even need to say that when I’m on stage: “You will never know what it feels like.” When people offer me empathy or sympathy, that’s great. Sometimes it feels better coming from other people because they do have this level of understanding what partner loss is or understanding what gun violence is or whatever. It doesn’t mean that one is more valid than the next, but it is helpful. This song, when I would talk about it on stage on tour, that song is so intense because it’s like [sings] “shotgun shells fill the wells.” It’s another cry for help. That’s so specifically about something. I could just feel the whole room shift every time, and it wasn’t bad, it’s just interesting to watch.

You’re inviting people into the truth of where you were when you wrote the song or are when you’re performing the song. Do you feel like you invite people into that space with you because if you didn’t it would feel disingenuous?

Yeah, I think about this a lot because I’m like, “I know who I am! I know what I’m doing! I don’t need to explain myself!” I’m just a very contextual person, but I do think that I’m constantly zooming out. When I’m offering someone to understand where this song or whatever came from—cause you could like it without knowing the context of it or whatever—it’s understanding that I am a person who is not just trying to exist in this world passively. As corny as it is, my art means something to me. My writing means something to me. It’s very thought-out. Sometimes it comes out faster than other times, where I just write a song and I didn’t even feel like I put effort into it. Sometimes it’s like months of working on it and having someone understand where it comes from makes it feel [like they] understand the full scope of what it is.

But yeah with the zooming out thing, I’m someone who’s very vulnerable, generally. It took me years of therapy and understanding who I am as a person and quitting drinking and all of these things to get to this point. And I’m looking at all of my friends and family and the people everywhere who just repress everything. I’m guilty of it too, but I’m terrified of watching my loved ones get sick from it. But me, splaying it all out—like on tour, honestly, every time I did it, it just felt like I was taking a dagger to my guts. Not in a way that’s bad, even though that sounds terrible. It's just like, I’ve really got nothing to lose. This is what I got. If you want to see it, if you don’t, I don’t care. Me offering you my story of where I am in the world, this is also an invitation for you to be open about your loss or grief or whatever you’re going through.

There’s this narrative, especially in the world that we exist in and the extended bubble, like DIY and whatever, this thing where we all have to be so in therapy and not “trauma dump” on our friends and we have to keep our shit together so that we can show up for this greater movement that is supposed to happen when we like. It just feels like this shame thing, like if we are not open with what is going on with us and we’re not reciprocating it, it’s like we’re not good enough. And that’s not, to me, how life works. Sometimes the pendulum is going to swing or whatever further to one side because your friend’s not doing good and they need someone. We just need to be more open with each other. I’m like such a communication guy. I’m like, why is my songwriting even connected to that? But it’s just so connected to me.

On Instagram, one day you were talking about joy and grief existing in the same breath. Not to tell you what you’re doing…

Tell me, tell me! I have no idea what I’m doing. [laughs]

But I hear so much joy in the delivery of these Makin’ Out songs that are so informed by loss. Do you feel that when you’re making a record with this band or performing with this band?

Definitely. Well one, I love melody and I love crust pop/pop punk melody. And I also love country music—all kinds, like really old and like ’80s and ’90s pop country, you know? And honestly, if you listen very closely to some of those melodies, you can hear it, which is really funny. But the joy in me, I’m very much a firm believer of multiple truths and I preach about it all the time and I think that writing songs that are horribly fucked up sad with these melodies that are like poppy sounding or whatever is a way for me, literally, to feel joy while I’m singing them. Playing music, playing guitar, and singing very loudly—having the vocal flipping and runs that I'm doing in the songs or whatever—just makes me feel physically good. That comes from that. My dog is snoring so intensely in the background. [laughs]

It is very much like the songs are me experiencing joy in the actual physical act of playing them, the expression of it, and also writing and putting those songs into words that still can relate to people on a general basis—universally. Walker, the drummer in Makin’ Out, you know Walker. He was talking to me the other night after practice because we just finished writing a new song that I’m really excited about. He was like, “You have a very cool way of writing these hyper-specific songs that are also just so universally felt.” I was like: “Wow. Yeah. Thanks!”

We’re at this moment for Minneapolis punk where so many DIY venues are getting shut down. Disgraceland, an active punk house for two decades, was recently sold by the property owner. [Ed. note: This conversation happened in May 2025. Disgraceland is a punk house once again.] You lived there, right?

I lived there for two and a half years I think, but I’ve been going there since I was like…17? Generally I’ve had a lot of friends who’ve lived there. Particularly with Disgraceland, it feels very sad. I used to go to Medusa, Secret Service, Coming Soon, all of these DIY spaces that have existed in the last like 14 years that I’ve been going to punk shows here. And I understand that things come to an end...very much so [laughs].

But it does feel particularly brutal. And I think for me, specifically, it’s because of watching the landscape change within the context of grief already. My brain is just so oriented to this 2023 summer with losing a slew of friends and then also August. Being like oh...things have changed so much. Since then, I have changed so much. And then watching Disgraceland go where it's like, Step Sister—my first punk band and the band I’m still in—started in that basement. I felt like I lived there even when I didn’t live there because all of my good friends lived there and everyone practiced there and we partied there and shows were there. It feels fucked. Seven people don’t live there anymore and now it’s going to sit empty for God knows how long.

It touches on watching the Minneapolis landscape change in general with the thousands of condos that have gone up in the 16 years that I’ve lived here. I don’t own a house. My family doesn’t own a house. Housing is going up just like everywhere else, and then like seeing these DIY spaces go—and the Artery’s gone and Nudieland is gone—it just is brutal. There are other things that will crop up and have cropped up already that I believe in and I’m stoked on. Any place that is willing to host punk shows on a regular basis? This is my hot take: You cannot complain about it. If someone is willing to host people, yeah, there could be problems. Don't get me wrong. It could be expensive. They could not do NOTAFLOF. They could not have good accessibility stuff, whatever. They could just be jerks. But it’s so far and few between, so we gotta believe in the spaces that are trying.

Basements and DIY spots in Minneapolis are wildly important. Houses were my introduction to punk shows around here. There was this show at House of Lard, I think Mystic Inane played...

Yeah, Mystic Inane did play, it was August 2019. I wasn’t there and I remember because I was really jealous. [laughs]

And then the last show I saw before COVID was Warm Bodies, Parsnip, and Citric Dummies but I can’t remember where.

It was at Riverboat. It was my birthday. October 3, 2019. It was my 25th birthday! [laughs] I’m not that crazy but I’m a little crazy.

OK so we’re establishing well, here—you were very much around. You were in the basements, going to the shows, but you weren’t actively in bands that entire time you’ve been going to shows. At what point were you like, “I want to be in a band”? When did that switch flip?

I think I was like literally a child. I’ve been wanting to be in bands my whole life, Evan, but I was so afraid. I give so much credit to Jon Adams [from Step Sister] for getting me to do it. And karaoke. I give karaoke and my drinking habit for a long time and Jon the biggest credits of pushing me into it.

I had such stage fright and was so anxious and not confident in myself whatsoever about anything for a very long time. When I was 23, Jon was like, I want to start another band. And I was like, Great. And he was like, I think you should sing in it. And I was like, I don’t think I should do that. And then he was like, But you know how to scream. And when I was drinking still, I was very loud. I still am loud, but I was much louder. [laughs] He was like, I think you can do it. And yeah, I did do it.

It took a long time to feel completely where I am at with it now, but I think specifically with Makin’ Out and playing guitar, I've always wanted to do that and I never thought I could. A lot of people [false murmur] specifically men are given guitars when they’re like 12 and [somebody’s] like you can do this and they’re like why yes I can! I also was given a guitar, a pink First Act, when I was in the sixth grade, and I just didn’t think I could do it. And I lived in a very small town of 600 people and tried to take guitar lessons and it just didn’t stick.

Where did you grow up?

I moved around a lot. Before I lived here, I lived in Gretna, Manitoba, Canada for five years—a town of 600 people. Before that I lived in Wyoming, before that I lived in Idaho, before that I lived in Minneapolis when I was two. But I was born in San Francisco.

What brought you back here?

We lived in Canada. My mom and her partner were splitting, and so we came here, cause it was the closest. I was 14 when we moved here, and my parents are punks. So my mom had friends here still and had lived, at different points of her life, has lived here. She’s always been like, “I’ve always come back to Minneapolis.” With the guitar, being young, I tried in 2019, I couldn’t do it, and finally it happened.

OK the tale of Makin’ Out, but bringing it back to that tour I was talking about, the tale of Makin’ Out goes back to a 2019 tour with Avery [Taylor] and Matt Jones and all my homies and they before they moved to Texas. I went on tour with them. I was going through a breakup and was like, “OK, I'll go on tour with six men for three weeks, that sounds good.” I ended up leaving the tour early. In the van and I was talking about how I wanted to start a crusty This is My Fist kind of vibe; a region rock-inspired and East Bay pop punk kind of vibe.

In the van, I was probably drunk, and I was like, “Makin’ Out is such a good pop punk band name.” And all the boys were like, “Yeah, that’s a really good pop punk band name.” I was like, yeah. And so this was in 2019. So six years ago, right? Makin’ Out has been a band now for two years. I tried to start it in 2019 with some people. I was just going to sing. They were playing guitar, but it didn’t stick. And I tried to start it again and again. And then finally it was like, “I just have to learn to play guitar myself. I don’t know how I’m going to do it. I don’t know how I’m going to make the songs sound like I want them to sound, but I’m going to figure it out.”

Can you tell me how you met the other members of Makin’ Out?

I met Walker 10 years ago now, pretty much. I knew him from being around, and then we worked together at Modern Times for multiple years. And then two years and some change ago, I was like, What if we started a band and you drummed in it? He was like, Yeah. I forgot honestly that he was a stand-up drummer. I don’t think I’ve actually told him that ever and now I just said that out loud. I knew. I’ve told this to Walker where Solid Attitude was one of my favorite punk bands when I was a teenager and they’re from Iowa City. I saw them play at House of Lard when I was like 17. If you would have told my teenage self “you're gonna play with a dude from Solid Attitude in a band,” I would have been like, “No, what are you talking about? I'm just a nerdy little teenager.”

Then Mike, aka Hot Dog. I met Mike in 2013 when he first moved here. Actually, I met him at a Halloween party at my house, which was a half block away from where we are currently. I’ve lived on this two-block radius like four times. He was dressed up like a hot dog at the Halloween party, so that’s why everyone’s been calling him Hot Dog forever. Our friend Leah Monson played bass for the first year and change, and then Hot Dog jumped on. We love Leah. We also love Hot Dog.

And then Naveen, I met in 2023. He was just around and I think there was a Step Sister show that happened at the Island, and afterwards, I was talking about how bad I want to be in a pop punk band. I love screaming in a hardcore band. I love it. I love thrashing around and being in it. But I call this band punky twangy pop. It’s really apt for what it is. If I say pop punk, someone’s always got a judgment on it.

Somebody’s got an idea of what that sound is.

They’re projecting. It’s the same thing when you think of hardcore with a capital H capital C hardcore. I’m not anti-genre, it’s just boring to me. But OK, so Naveen is an incredible shredder. Loves Bay Area pop punk and region rock stuff. He was like, I’m down. I knew Naveen was a shredder, but I didn’t know the caliber of shredding he was capable of.

I was like, “Wait…I actually did it. I asked the right people.” Still to this day, I can bring a song and we have it pretty much worked out by the end of practice. I’ll bring like a full or partial song and then we’ll flesh it out together pretty immediately. But the first five practices, we would leave like glowing, and that was before we even had a bassist. We just fell in line with each other.

And they’re so open to my bullshit. Especially in the beginning, we started practicing like pretty soon after August was killed and I would like start crying in the middle of practice because it’s fucking hard.

But that’s not bullshit.

No but then also there’s also a lot of bullshit because I’m a little neurotic, I would say, and also I'm in two bands with all dudes and I live with all men and I love them, dearly. Love them but sometimes I’m just like: Oh my god you guys!! What is going on?!

Just surrounded by specific dude energy all the time?

Yeah, and it’s not even a slight. They’re all so wonderful, but sometimes it’s like: I can see you’re not listening to what I’m saying right now. And that’s not just dudes, it’s just people. Sometimes it’s hard. Also, it’s a lot. One of the members of Makin’ Out was at the shooting. Multiple of Step Sister members were at the shooting. I’m not trying to say that this is necessarily what people have told me time and time again, but I know that I am a walking reminder of it in this way that can be hard. People, for two years, were very used to August standing next to me. I have his art on my body. I sing songs about him.

I’m not trying to live in this way that is dwelling-upon. I’m trying to live life in a generative grief-centered way; generative grief in a way that’s like I’m propelling off of it, I’m moving alongside it, I’m using it as a tool to further understand the living that is around me. Being in a band with people within that, I can understand where that can be hard because I’m a little intense. It’s chill. I just have a lot of gratitude for them, you know?

I get that when you write songs and play them out, the next natural step is to record them. With songs like these, though, can you talk me through why it was important for you to make an album?

I didn't know that for the last couple years I was writing a record. And I think that would have been the ultimate goal because it just feels really cool, especially with the timing with Outta Wax opening and also Dead Broke had pursued me about releasing something and I was like, “Well, I want to put out a record. If you’re willing to help with that, that would mean the world.” And also, I’m just kind of a go big or don’t go at all kind of person. I don't go home, but I’m just like, nah. My therapist is always like, “You’re kind of all in or not in at all.”

This record wouldn’t exist without August in general, but also wouldn’t exist in this way if he hadn’t died, which is a really crazy reckoning. But because Nudieland reverberated so hard and him being my partner and being there and watching it happen. I didn’t get shot or even see him get shot or watch anyone get shot because I turned around in that moment—I still got like more money than I’ve ever seen in my entire life and I probably will ever see in my entire life at one time, which is like a very complicated thing.

Through donations?

Through donations. A good friend set up a Gofundme the day after, and I guess you could say it went viral or whatever. People really showed up and I was like, “OK, well I’m going to travel to see people that I love and grieve and be far away from this place, which was really hard to be in for a long time. And also...release my music. I know that August would be stoked because he was my biggest fan. Like he was just so nerdy about it.

He was stoked!

Yeah, he was! He knew the lyrics to songs and didn’t teach me how to play guitar but I wouldn’t have done it without him. He’s an amazing guitarist and our bands are cut from the same cloth in a lot of ways, I think just based on both of our tastes in music and stuff.

So it was just me wanting to be like, Cool I fucking did it. Look at me! I’ve had a horrible time in the last year and a half and I’ve also had a wonderful time. I’ve done more in the last year and a half with my life than I ever have ever. This year will be five years that I quit drinking and it’ll be two years since August was killed, which is the same day, which is psychotic. My sobriety day is the same day he was killed, but a few years apart.

I feel like with sobriety specifically—abstaining alcohol or whatever—it’s this thing where you’re constantly overcoming milestones and chapters opening and closing. And this is a chapter. This is another big milestone, and it’s in line with the hearings and it’s in line with his birthday, which was just the other day. It’s in line with all these things. I’m obviously very date-oriented. [laughs] I remember dates easily for some reason. I can’t remember a bunch of my friend’s birthdays now, but I can remember the day of a show in 2019.

It's just my way of being like: Fuck all of you. [laughs] This is what I did and this is what I have. I’m not letting it take away my life. It happened at a punk show and it happened in his backyard—in every intersection of my life and livelihood. I don’t want that to be what defines me forever, you know?

What do you think your future chapters look like? Do you believe in manifesting or forecasting or do you just move?

I think that I move with intention in this way that I’m paying attention to what’s going on around me—as much as it doesn’t seem like that sometimes. I talk a lot about synchronicities and the psychotic synchronicities that are happening around me all the time. I have lots of friends who’ve experienced partner loss and grief in really fucked up ways. Or have experienced grief because of really bad tragedy. I think synchronicity stuff is so weird and real. It’s not manifesting, it’s just paying attention. I don’t know if I believe in manifestation, but I do believe in the times I’m like “this is probably happening, this is this other thing is probably gonna happen,” and then I’m right. Then it’s like I’m losing my mind clearly because this is so weird.

But I do know that with this the record being the biggest thing so far, it’s just the beginning. I have a record’s worth of other songs between my solo stuff and and Makin’ Out. I have seen my songwriting shift even just from a lot of these songs being written from the beginning and from me starting to play three years ago and I think that I just want to keep doing it.

There’s nothing else that feels as grounding and reassuring. It feels like I’m connected to myself and other parts of my life that I’ve experienced because of these songs. And I actively think about what was happening around me, while I’m playing them live, when I was writing it. That means it brings me back to places with August or other friends who have passed. I’ve written a bunch of these songs post-August dying, and I’m going to keep doing that. It just helps me remember my life and keeps me going. I’m gonna keep going. I’m going to keep doing it. I just wanna keep doing it. [laughs]

see/saw is a reader-supported publication, so if you enjoyed this feature, please consider subscribing.