peace de résistance’s moses brown + the art of solo project glam sleaze

A discussion about punks going solo and leaning into glam personas + feeling like an old curmudgeon for as long as he can remember.

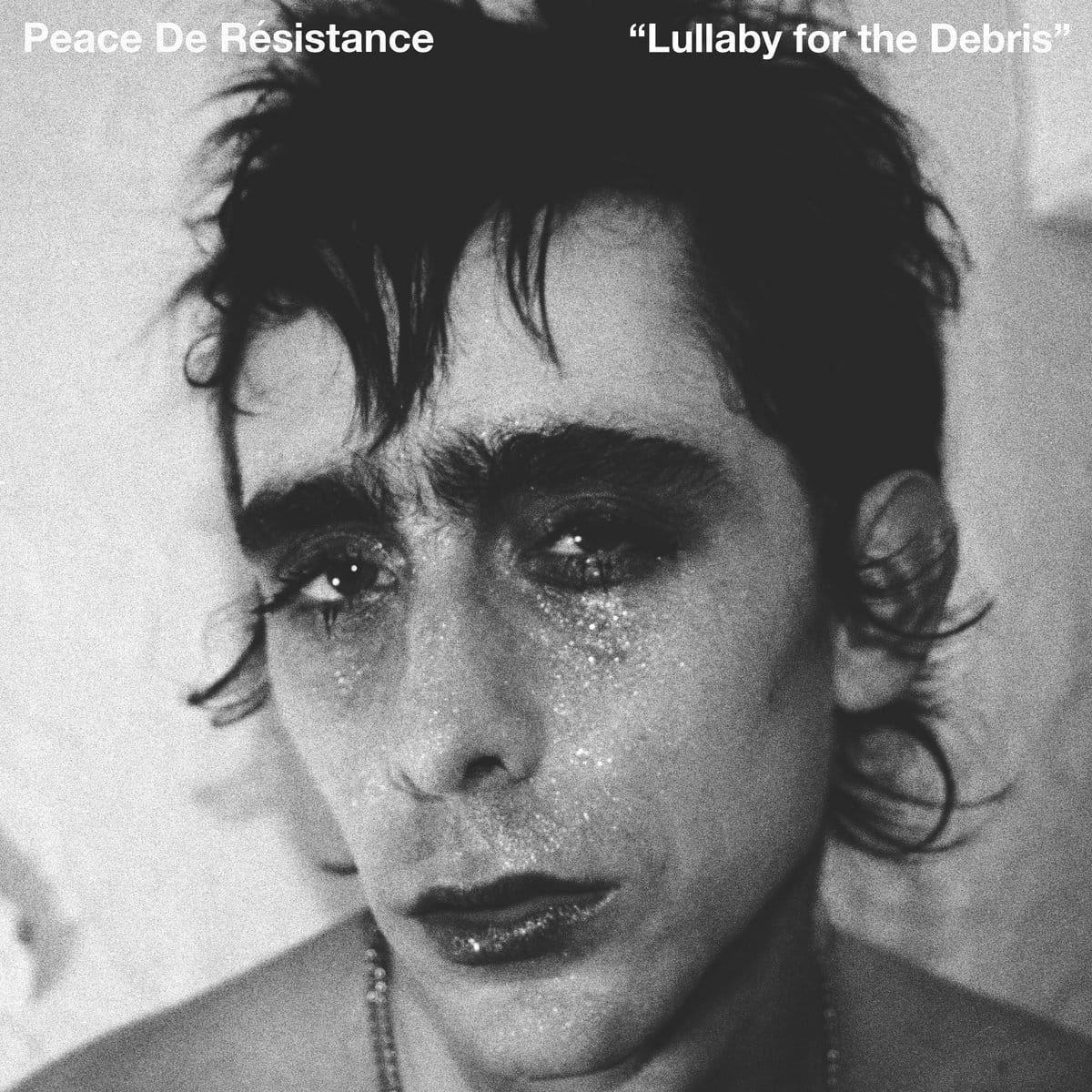

Peace de Résistance plays into the sleaziness and glamor of a frontman-gone-solo from a bygone era. “As soon as the punks leave the punk band they lean into the glam,” says Moses Brown, the brain behind Peace de Résistance. His solo work departs from the dirty anarcho punk rock of Institute, a band he’s been part of for over a decade. It slows the pace in favor of a moody funk, rich soundscapes and vintage rock‘n’roll riffs with a more dramatic flair.

Brown started Peace de Résistance in the height of the isolation of the pandemic when making music with others wasn’t an option. In his home studio, Brown began toying around with new sounds: “It was an excuse to just do the things that I always wanted to do in a band but that seemed too crazy.” That experimentation led to the release of his first solo record Bits and Pieces in 2022. Lullaby for the Debris is his sophomore release on La Vida Es Un Mus, and it takes the sonic foundations of Bits and Pieces a step further.

Listening to Lullaby for the Debris can feel like time travel, as the record nods to Bowie, Lou Reed and zamrock. It’s the kind of thing you’d hear walking into CBGBs in 1975. And Brown is singing about the same kinds of recessions experienced in the mid-’70s on tracks like “Pay Us More” in which his words slither over a hazy rush of textures: “It’s hard to make a living when they don’t pay a living wage.”

The lyrics feel painfully relevant at a time when monopolies like LiveNation and Ticketmaster are working overtime to make the profession of ‘full-time musician’ an extinct career. “If you want to be successful you have to either work a ton and then go on tour, which is great, or you have to completely buy in and just be on the road for six months of the year,” says Brown. “That feels impossible.”

Brown chatted over Zoom about working alone, creating in the online era, writing lyrics for two different projects, and being born old.

You have a new record and you started this project during 2020. Now that you don’t necessarily have to be alone making music by yourself, what has been kind of like your drive in keeping this solo project?

Moses Brown: The pandemic forced me to make music by myself. When that happened, I kind of realized that it was amazing. I can just do whatever I want. So that kind of unlocked something, and it was an excuse to do the things that I always wanted to do in a band but that seemed too crazy. And having been in Institute and Glue recording records in studios with limited amounts of time, having a whole home recording studio and just having unlimited studio time has been huge too.

When you have total control and unlimited time to work on things, how do you know when something is done or how do you decide when you have to walk away from the song you’re working on?

Right, I mean like I’ve talked to so many people, I have so many friends that have hours of music that are unfinished. And I don't know, for some reason I’m a really good finisher. I just like to wrap things up, and I don’t want these ghosts of songs just sitting around half done. I’d much rather them be done or gone, you know? So I'm just trying to close songs down. And at a certain point too, a song is all it can be. You're like, OK, ‘I've tried X, Y, and Z. The song is essentially just this.’ So let's just end it, let's just be done with it. We're cutting it off.

When you’re writing the song, are you doing them in bursts or do you kind of skeleton something and then come back to it later?

Yeah, I usually skeleton something. And then, you know, work on it for 60 hours. A good day, I could record a guitar track and then start trying to do bass or something else on top of it. But that’s usually as much as I can get done before I get burnt. I have to walk away.

How do you recharge?

Usually I’m trying to just go see people, go to a show. Ideally I’m going to the beach. But there’s some studio days where you’re just kind of stuck at your house. If I need a break I end up reading or watching skateboarding videos.

Sick. Do you skate?

I do, but I’m just so bad now.

I watch a lot of skate videos. In particular, I’ve been watching a lot of quad skating. Those soundtracks, like the music that people are picking, are so good. Recently people are using more retro music, which has been super fun, because I feel like it’s making me revisit things that I haven’t thought about in a while.

Yeah, there’s lots of like 2003 Midwest emo going on. It's like, whoa, I didn’t know this Saetia song was going to be in here, that’s cool.

Maybe one of your songs on this album will turn up in a skate video.

That would be great, yeah.

Has that ever happened?

I don’t think the skaters are really listening to it. They’re listening to Dollhouse or something. I’m the old guy rocker, you know?

I don't think you count as an old guy yet.

Yeah, that’s true. But maybe in spirit, I think I do.

How long have you been old?

Oh my God, I’ve been old forever. I remember being like 22 and a couple of friends that were in their thirties would just be like, you’re the only one I could talk to. Like, you’re so young, but you’re old. Not wise; I’m just kind of like a curmudgeon. Like I want to go to bed.

I like that you clarified: no wisdom.

No, no—no wisdom. No, no, no. Definitely not.

You came out the womb a little jaded and a little tired.

Exactly, yeah.

This project has a pretty strong visual identity like the photography matches the energy of the record really well, so I’m curious if you’re thinking about the visuals when you’re writing the songs or if that comes later?

There’s just like a certain level of sleaze that I’m shooting for you. Sleaze and glamour, so definitely that's a factor when I’m writing the songs: Is this gonna match the makeup and the weird face on the front of the record? Having it being so photo driven was kind of a response [to Institute] because obviously with the Institute record I know I’m gonna draw something. At the start of [Peace de Résistance] I was like, “Am I gonna draw something for this? Do I have to learn a new visual language of text for this band?”

But then obviously it's a solo record of a punk, so like let’s just like play to the trope and have makeup on the face. I love when people go solo. I can’t really think of a perfect example, but people leaving their bands and going solo, especially punks, and just like leaning into it—I love when punks go solo. Like Nikki Sudden. As soon as the punks leave the punk band they lean into the glam. Leaving the pack and becoming like a whole individual main character.

It’s interesting that you have this solo project that’s leaning into that sleaze and glam has a strong visual element because you don't play shows. Unless that's changed?

Still no, no plans. It still doesn’t make sense.

You’ve previously mentioned that you spend all this time in the studio and you can freely add to it because you’re not thinking like how does this apply to a live performance.

Exactly. I don’t have to worry about recreating it live, like hypothetically if I had a half an hour of songs that would translate well live I’ll be like, “Fuck it!” I don’t have that, and I don’t know if I will have that.

I feel like you’re someone who’s thinking about the state of the world, what it means to be like a person who exists in this capitalistic society, so I’m kind of curious when you’re writing the lyrics for this, how do you balance wanting to speak about those experiences in your music while also not wanting to get in the weeds?

With Institute, like specifically Readjusting the Locks, I listen to songs on that [record] now like “What is this song even about?” It's me just reading and absorbing and watching all this heady critique of capitalism I guess, and then I’m trying to regurgitate that. It comes off as you don't know what you're talking about. I tried to tackle big issues or a big overarching thing on that record and it didn't work for me. It’s like I don’t know what I’m talking about.

And so for this project, I was like, “OK, I'm just gonna talk about what I know.” I’m just gonna talk about things that I see every day and things that I've experienced. And that felt way better. Like, I'm gonna do a song about paying rent. I’m gonna do a song about going to the pharmacy. I’m gonna do a song about going back to the town that you grew up in. Just approaching these big subjects that we all feel, but from my more layman perspective, and not to sing about things where I don’t know what I’m talking about.

I think you kind of just spoke to it, but you’re writing lyrics for more than one project. So is the process different?

Hmm, it’s hard. I mean, the last Institute record that came out, Ragdoll Dance, it was like, “Oh, hmm. I don’t know what to do right now.” But that was fun. I just kind of tried to do a mix. It was just freeform. I was like “I just want to have fun,” and so I did.

Are there any songs that you recorded that didn’t end up on this record?

Yeah I mean there’s just a bunch of half finished songs, usually I’ll bail on something halfway through if it’s not gonna work out.

You can sense it?

Yeah totally, I’m just like “this is boring” so I just cut it.

It's almost easier then because then you don't have to pick what goes on the record, you just know what worked and what didn't.

Exactly, yeah, it’s like propagating seeds or whatever. I got 18 seeds and only nine of them are actually going to make it to the plant stage.

Do you let people in during the process, like does anyone hear these songs before they become the record?

Yeah, I’ll play a couple things for some friends, maybe just to get some ideas or just be like ”Is this boring?,” “Is this working?” But for the most part not really. So it's kind of like a surprise.

What is your take on this moment right now where musicians are sometimes being expected to also be online figures? How do you navigate that given that that's not something that you want to do?

I mean, I don’t know. I hear stories about people, like I have friends that work at some of the bigger indie record labels or whatever, and the stuff that you have to do as an artist now, it’s crazy. You have to engage with people and do personalized things. I’m like, “This is so bad.” Like as if musicians weren’t already kind of just like a play thing for people, now they really are.

When I listened to this record, I listened to it with headphones front to back and I was like, “Wow this is a great record!” And then I thought about it in the context of the greater, very broken music industry. How does anyone get a really great record out to people?

I have no clue. Without engaging in this super ass backwards industry? I don’t know, it’s bad. Ten years ago I think you could, there was that sweet spot of like 2008 to 2014 where a bunch of more scrappy punk bands were getting attention, but now to get that kind of attention you have to make compromises. That being said though, there’s a lot of faceless producer people that’ll just drop something on Spotify and all of a sudden have like a million listens, so it can happen, seemingly.

So that’s literally not what you're thinking about. You’re just thinking about making the music.

Oh yeah. I think about it being on a record and my friends buying it and that’s about as far as I go.

Is there anything about this project or this record that you want people to know that I haven’t touched on?

It’s just me sitting in a room.

Do you have the makeup on while you’re recording?

No! Hell no. I got, like, shorts and a funny shirt on.

see/saw is a reader-supported publication. If you enjoyed this article, please consider a paid subscription to support this independent punk journalism operation.